In an era where the avant garde movements of Europe wanted to stray away from traditional representation and realism in favour of a more abstracted, political artwork, New Objectivity ceased photography and the photo-book as its medium and created work that was born out of stark realism. Photographers like August Sander, Albert Renger-Patzsch and Karl Blossfeldt created narratives through images in their photo books, taking art out of the gallery space and into the sphere of the general public. The 'objective' nature of New Objectivity would suggest an un-biased nature to the movement, where the aesthetics of the object represented and the careful, often contrasting or thematic juxtaposition of these images said more than any underlying politics that influenced them. However, by using Michael Jennings text on photo-books in the Wiemar Republic, we can see how these objective and aesthetic images can have a more politically charged meaning when they are synthesised into a photo-book.

Looking at August Sander's The Face of Our Time from 1929, a selection of full age single and group portraits show a range of classes in their normal environments, starting with agriculture workers and moving thematic and systematically through urban workers, revolutionaries and capital workers. Sander's book ultimately has a focus on the population of the city, and this line of movement is symbolic of the changes that are occurring in Weimar Germany, where the city and industry are expanding. For Jennings, The Face of Our Time is both synchronic and diachronic, meaning that it is both of its time as well as charting social and historical development. Taken out of context of the photo book, the photographs are objective depictions of the everyday lives, clothes and environments of those pictured, whether it be a butcher, farmer or tycoon. When seen together in this format however, they images take on a diachronic aspect, where they track social and historical changes throughout time, starting with the dependence on the land and moving towards a higher dependence on industry and the city. 'Photography is a mosaic that becomes a synthesis only when it is presented en masse' is a way that Sander's describes the importance of the photo book, and the way that it mobilises become a diachronic piece with the ability to encapsulate society.

Straying away from people completely and focusing an interest more on the tensions of nature and industry, Renger-Patzsch's infamous photo-book The World is Beautiful from 1928 has an array of photographs that range from extreme close-ups of flowers to industrial tools and architecture. The focus on industrial photography is for Walter Benjamin and subversion of the human labour that created the commodities that Renger-Patzsch photographs, and for this reason he is emphatically against The World is Beautiful. Even the name, for Benjamin, removes all of these social relations that have come to create the commodity, however it was at the discretion of the publisher Kurt Wolff to call the photo book The World is Beautiful rather that Things which was Renger-Patzsch original vision. However, if we use Nietzsch's 'chaos theory' we can make some interesting conclusions with regards to The World is Beautiful. In chaos theory, seemingly meaningless and random events can create an enormous result when considered in retrospect. Are Renger-Patzsch's selection of images and juxtaposition of natural and synthetic images making a statement about Weimar Germany's focus on industrialisation when viewed as a synthesis of images in retrospect, or are they merely grouped due to their formal similarities, with little underlying political statement?

An irony that occurs in Benjamin's reception of the photo book occurs when we see the praise that Art Forms in Nature by Bloosfeldt received. The book which consists of close up, detail photographs of flowers and plants against a white or grey background was seen by Benjamin as hosting a great amount of artistic licence, as the photographs use tonal depth to create forms that seem almost sculptural and architectural. Ironic because the similar photographs of enlarged flowers seen by Renger-Patzsch didn't warrant the same reaction despite their similarities. The viewing of these images is described by Renger-Patzsch as 'joy before the object', where we have a strong aesthetic reaction to these uncanny objects due to the formal photographic techniques of visceral surface detail and depth of shadowing. These close-ups offer the viewer a perspective that they are not used to seeing, and gives us a sense of the camera being an extension of the human eye.

Images to use:

Thursday, 23 April 2015

#revision - BAUHAUS AND MAHOLY-NAGY

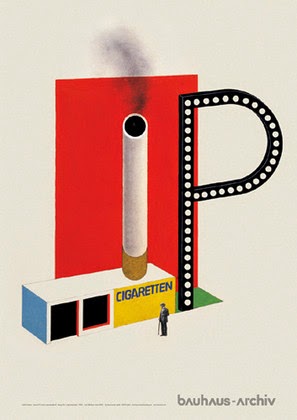

In the inter-war period, Germany was ripe for avant garde movements. The Bauhaus was started by Architect Walter Gropius in 1919 as a school that would ultimately create an all encompassing artist - 'the artist, the craftsman and the technician must become one' was a key belief of Gropius. Architecture, furniture and photography became a key areas of deign covered by the Bauhaus, and collectivised villages were created with minimalist, geometric furniture in open plan living space. This idea of collectivisation seems extreme and almost politically charged, but its aim was to remove the isolated individual instead of submit any political ideologies. The Bauhaus was based more on the belief of brining art and design into the everyday rather than politically revolution through art. Artists like Herbert Bayer designed colossal, colourful, geometric kiosks that were not realised but instead lived their life as illustrations. The images from 1924 exist as huge monuments in colourful print that dwarf the illustrated visitor. The fact that kiosks were redesigned showed the Bauhaus' desire to redesign everything in life.

An artist that wanted to redesign the way that we think about art by changing the way photography works was Lazlo Maholy-Nagy. Instead of trying to imitate art like many photographers have done, it is 'unimportant whether photography produces art or not' for Maholy-Nagy, as the mediums future worth should be what photography decides it value by. This reason is why Maholy-Nagy decides to over-perspectivise his photos, where there are multiple or extreme perspectives that at first confuse the viewer and make strange what is being depicted. Berlin Radio Tower from 1928 is a photograph taken from a birds eye viewer atop the tower, with the structure of the tower itself entering into the frame. This vertiginous metal framework appears to go on endlessly in either direction, into the ground and sky, and at once confuses and makes strange the object represented. The shadows from the settings sun are long and spread across the landscape, offering another angle of perspective. Maholy-Nagy was often criticised by his avant garde counterparts as being uncommited to any political motive in his photography, which ultimately make him as bad as the traditional artists that came before him. Devin Fore uses theories of perspective through time to understand whether this claim is true, as unlike the Constructivists or Dada, who completely negate all perspective from their work, Maholy-Nagy uses multiple perspectives. Linear perspective has come to be seen as something that is tied up in the romantic ideals of art, and to use in art during the avant garde could be seen as compliance with these traditional values. For Fore however, the artists over use of perspective still negates traditional art, as it uses its own means of rational to confuse itself.

Leda and the Swan from 1925 is a form of collage that uses the white plane as a perspectival background, with the collage forming an 'organised chaos' on the clean plane of vision. This 'chaos' offers the viewer a type of representational organisation with coherent depth and spatial volume. Instead of calling these 'photomontages', Maholy-Nagy calls them 'photoplastics', as they have much more coherence than the usual montages of the avant garde.

Images to use:

Wednesday, 22 April 2015

#revision - DADA

The Constructivists in Russia aimed to create a form of art that was in line with communist values and was available for everyone. The same could be said for Dada, however these artists were influenced by mass media, advertising and the mass commodity, which ultimately used capitalist modes of representation against itself. Artists like John Heartfield, George Grosz, Hannah Hoch and Raoul Haussman created imagery that was pro-revolutionary and anti-bourgeoisie, whilst also offering a satirical undertone.

As with many of the avant gardes, photography was utilised for its reproducibility. Artists like Hoch utilised images from mass circulated newspapers and magazines which she then collaged together to make a critique of capitalist culture. In Dada Panorama from 1919, images of the current Wiemar president wearing wellington boots are taken out of context and made strange by Hoch's placement of various other detritus of magazines and commodity culture. Hoch's technique is very layered and disjunctive, and through this technique of breaking up conventional representation, a type of subversive reality can be formed. Heartfield in particular utilises this creation of an alternative reality, but does so seamlessly. Sabine Kriebel writes about Heartfield's slaved over AIZ journal covers, which offer altered reality that is formed through seamless photomontage. This seamlessness was critised as being too reliant on formal representation by Contructivist Gustav Klutsis, however Kriebel counters this with a declaration that the ability to understand the work in such a way makes it a serious political weapon for its directness and satire.

Heartfield's utilisation of AIZ is important for the mass circulation of Dada art. AIZ is just one of many journals that were used by Dada artists, some which include Neue Jugend or the self-created 'Dada'. By engaging with these modes of circulation, the individual originality is taken away from the artwork, or as Benjamin would say the 'aura' is lost, and the works continue to exist in the world in mass. This is good for artworks that are influenced and have strong associations with propaganda and advertising, as the are made for educating the public in much the same way that political posters and campaigns do. In Millions Stand Behind Me from 1932, Heartfield engages with the political with a direct reference to Hitler's quote 'Millions stand behind me' - the millions in Hitler's case meaning the population, which Heartfield has subverted by placing a large banker putting money into Hitler's saluted arm. The clever play on words is engaging, whilst the political tone of the piece is aiming to educate the population on fascism.

As well as propaganda, advertising was important part of these artists influences. Heartfield, Grosz and Hoch all studied applied design or worked in advertising before turning to art, and therefore have a good idea of how to make an engaging work. Sherwin Simmons believes that Dada has a complex relationship with the mass commodity, in which they are working for a socialist future but using capitalist means to create it. Grosz and Heartfield presented themselves as 'manufactures of the commodity' by creating artistic greetings cards, adapting their style to suit their market for a pure exchange value. For Sherwin, by doing this the artists are 'problematising the commodity' - showing the ease at which it is possible to manipulate the market and the buyer in a capitalist society. This relationship with mass culture has come to be a trope of Dada.

As stated in earlier posts, the desire to bring art into life and life into art is a key part of the avant garde. As well as mass circulated images and the use of photography, the Dada artists also engaged with real life visuals instead of creating these montaged 'alternative realities'. After WWI, the amputee was a new visual phenomena that artists engaged with as a means of going against capitalism. Ernst Freidricks' War Against War book from 1924 showcases gruesome but frank images of the damage caused to humans due to war, stating that to 'fight against capitalism is to fight against any war' - for Freidricks, the reality of war is caused through the presence of capitalism. Grosz also directly addresses capitalisms engagement with war - in 1920 he painted War Cripples, which showed a line of war cripples on the street. This was a reality for post-war Germany, and to engage to explicitly with these visuals was an obvious anti-capitalist stance.

Images to use:

#revision - CONSTRUCTIVISM

After the October Revolution of 1917 and the overthrowing of the Tsarist regime, the Marx influenced Bolsheviks rose to power, led by Lenin. This new communist regime saw the beginning of a new type of art, that followed the avant garde praxis of brining life and into art and art into life. Through the use of photography and photo montage, to the designing of furniture and architecture, the Constructivists rethought how art and design can be integrated into life. The role of the artist was also evaluated, with El Lissitzky pushing for the artist to be an engineer and a constructor and not exist in the role of the 'genius-artist' that had come to plague art history. The communist government demanded a new social type of art, and artists like Alexander Rodchenko, Gustav Klutsis and El Lissitzky made this possible.

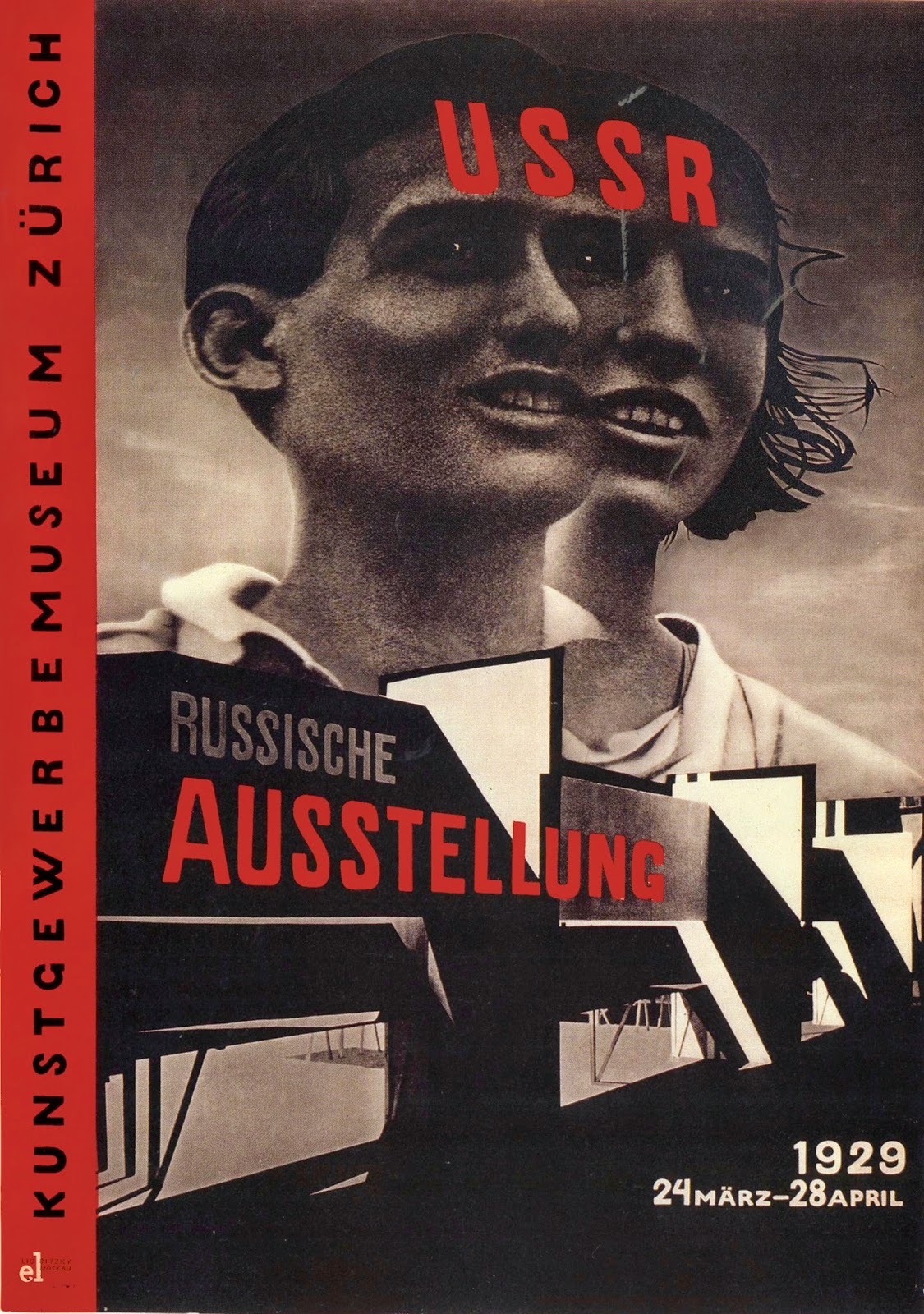

Just like the Futurists cultivated photography in their work, in Russia it became a popular medium. Osip Brik writes that photography is a more social medium, with the 'most expensive camera is still less than the cheapest painting'. For this reason, it was adopted as a new social art form, alonsgide its ability to be reproduced. Walter Benjamin highlights the importance of the ability to mechanically reproduce, and it is this reproducibility that was necessary for artists like Lissitzky and Klutsis who created posters that supported the communist government. In Klutsis' Let us Fulfill the Plan of the Great Projects from 1930, the artist uses his own hand as the focus of the montage, filled with copies of hands holding a salute. The anonymous nature of the hand allows any viewer to position themselves in the salute, and the action places the viewer in line with the communist government. A strong use of red further emphasises this connection, as does the name of the piece. Created as a poster, the ability to reproduce and be circulated is crucial to the meaning of the work - Russia had a very spread out population with high levels of illiteracy, and have a mass circulated and direct visual made this work very social. Lissitzky also uses photo montage to create posters that support the Bolsheviks, shown in his Russian Exhibition Poster from 1929, which layers the faces of both a female and a male to show the equality of the workers. Much like the Russian pavilion at the 1937 Paris International Exposition, which depicts a man and woman striding forward atop of huge column, the creation of equality in the sexes was important for communism.

The Russian Pavilion was important for signifying the desires of the Bolshevik government to the rest of the world, and was a architectural feat. Architecture was an extremely visual way of differentiating between the old and the new, and something that we can see in the ideals of Vladimir Tatlin's Monument to the Third International from 1919 which was never realised. Created from metal and glass instead of brick and mortar, this moving building was envisaged to be taller than the Eiffel tower. The movement in this monumental building was built to work was a clock, the start date 1917, symbolic of the October Revolution and the beginning of a new regime. Whilst this building was never realised (a saddening trope of the avant garde and it's desire for a utopia that ends up being missed), the photograph that was created to mimic its appearance places the traditional architecture of St Petersberg behind, emphasising the difference between the old and the new.

The artist also had a change in role, from one of genius to one of engineer. We need only look at the self portraits of two leading artists, Lissitzky and Rodchenko to see how they try and make this differentiation. In Rodchenko's self portrait photograph from 1922, we see the artist wearing a boiler suit and holding a pipe - he is taken out of the romantic ideals of the studio and put in an industrial setting, aligning him with the workers both visually and physically. Lissitzky's is very much the same in that it has a desire to show the artist as a constructor. The Constructor from 1924 is a montage of graph paper, a hand holding a compass, the end of the alphabet all over laying the artists face. Instead of an eye, the artists compass holding hand replaces, showing that the work now comes from the hand, and the mechanisms of creating perfect geometric shapes, rather than the idealised vision of the artist. The graph paper is further showing the importance of geometry and rational thought, whilst the end letter of the alphabet could be symbolic of the end of the past era, making way for a new Bolshevik art form.

Images to use:

Monday, 20 April 2015

#revision - FUTURISM

One of the most aggressively nihilistic of the avant garde movements has to be Futurism. From the violent and assertive language in their manifestos through to their fascination with war, the Futurists put their hopes in a technological future that completely destroyed traditional Italian aesthetics that came before hand. The movement began with F.T Marinetti's 1909 Futurist Manifesto that featured in La Figaro, the first amongst hundreds of manifestos that came to define the movement. In Marinetti's writing, we see the artist being re-born from a ditch into a world where technology overrides tradition, where humans have 'electric hearts' and their nerves 'demand war and despise women'. These few quotes outline the sexist and fascist undertones that the Futurists have come to be defined by, whilst also attempting to 'naturise technology and technologise nature' as Hal Foster has recently posited.

Foster tells that this desire of the Futurists to 'technologise nature' was born out of the aftermath of the wars, which showed the human bodies last of resilience to weaponry. It was time to re-think the human body and to fuse it with technology such as auto mobiles and weapons which have shown to be advanced and powerful. Bruno Munari's And thus we should set about seeking an aeroplane woman from 1939 uses photomontage to create a woman/aeroplane hybrid, showing the extreme lengths that the Futurists went to to achieve a technologised human. Even more poignant is the fact that this is a woman, which Futurists had negative feelings towards - the female gender was intertwined with ideas of nature, and therefore went against the Futurists assertion that technology was the way forward. By creating a woman out of technology, she has become far removed from the stigma of being a female that carries notions of nature.

Ideas of speed and movement were also key to the work of the Futurists, who aimed to capture dynamism or sound in their works. Chronophotography by Anton Bragaglia presented to the Futurists a form of photodynamism, where movement and speed that would usually miss the eye are caught by a camera. In The Smoker from 1911, Bragaglia captures the slow and leisurely movements of a smokers hand moving up and down, the smoke create a haze around the face. The process of the action is caught, and it is more about this movement than the subject matter that made chronophotograpy popular within Fascism. Artists like Giacomo Balla tried to capture this speed and movement on the canvas. In The Car Has Passed from 1913, visceral swoops of white and blue fragment the canvas, symbolic of the fast movement of a car that is already out of frame. The representation of the car is too fast for classic painting to pick up, racing ahead of the traditional medium, and leaving behind a trail of waves.

Movement was also captured through painterly techniques. Umberto Boccioni used divisionism in his 1910 painting The City Rises, which consists of using little strokes or dots of colour to create a dissolved effect, which give the impression of movement. By titling the figures represented at strong angles, the sense of movement is heightened. The City Rises depicts a scene of construction, where workers and horses are seen to be in a flurry of movement, and scaffolding and cranes appear in the background. It can be seen as portraying the industrialisation and technologisation of Italy that the Futurists wanted, yet the use of horses is reminiscent of the old ways of construction.

The Futurists wanted to distance themselves from the past in much stronger ways than any of the other avant gardes. Marinetti calls of the destruction of libraries and museums, 'tombs' of bourgeois consumption in a bid to move forward and create works of art that focus not on Italian classicism but instead on a bright future. Even despite being tied up with fascist links, Marinetti began to distance himself from Mussolini when the dictator started focusing on Classical Italian art.

Images to use:

Foster tells that this desire of the Futurists to 'technologise nature' was born out of the aftermath of the wars, which showed the human bodies last of resilience to weaponry. It was time to re-think the human body and to fuse it with technology such as auto mobiles and weapons which have shown to be advanced and powerful. Bruno Munari's And thus we should set about seeking an aeroplane woman from 1939 uses photomontage to create a woman/aeroplane hybrid, showing the extreme lengths that the Futurists went to to achieve a technologised human. Even more poignant is the fact that this is a woman, which Futurists had negative feelings towards - the female gender was intertwined with ideas of nature, and therefore went against the Futurists assertion that technology was the way forward. By creating a woman out of technology, she has become far removed from the stigma of being a female that carries notions of nature.

Ideas of speed and movement were also key to the work of the Futurists, who aimed to capture dynamism or sound in their works. Chronophotography by Anton Bragaglia presented to the Futurists a form of photodynamism, where movement and speed that would usually miss the eye are caught by a camera. In The Smoker from 1911, Bragaglia captures the slow and leisurely movements of a smokers hand moving up and down, the smoke create a haze around the face. The process of the action is caught, and it is more about this movement than the subject matter that made chronophotograpy popular within Fascism. Artists like Giacomo Balla tried to capture this speed and movement on the canvas. In The Car Has Passed from 1913, visceral swoops of white and blue fragment the canvas, symbolic of the fast movement of a car that is already out of frame. The representation of the car is too fast for classic painting to pick up, racing ahead of the traditional medium, and leaving behind a trail of waves.

Movement was also captured through painterly techniques. Umberto Boccioni used divisionism in his 1910 painting The City Rises, which consists of using little strokes or dots of colour to create a dissolved effect, which give the impression of movement. By titling the figures represented at strong angles, the sense of movement is heightened. The City Rises depicts a scene of construction, where workers and horses are seen to be in a flurry of movement, and scaffolding and cranes appear in the background. It can be seen as portraying the industrialisation and technologisation of Italy that the Futurists wanted, yet the use of horses is reminiscent of the old ways of construction.

The Futurists wanted to distance themselves from the past in much stronger ways than any of the other avant gardes. Marinetti calls of the destruction of libraries and museums, 'tombs' of bourgeois consumption in a bid to move forward and create works of art that focus not on Italian classicism but instead on a bright future. Even despite being tied up with fascist links, Marinetti began to distance himself from Mussolini when the dictator started focusing on Classical Italian art.

Images to use:

#revision - THE THEORY OF THE AVANTGARDE

Many of my past posts have touched on the avant garde and the neo avant garde, but in this post I would like to cumulate two of my courses to talk about theories of the avant garde. What does the term mean exactly? Was in successful and what were its main features? All of these questions are vital to our understanding of the term, and to understand that helps our understanding of many movements from the 20th century.

The avant garde has been hotly debated over by critics during the last century, with many of them have different opinions on its impact and influences. Whilst Rosalind Krauss believes originality to be at the centre of the avant garde, T.J Clark counters this stating that if originality was at the heart of the practice then, the repetitive nature of their works negates the concept. This 'originality' is born out of a political and social desire to go against tradition, and when your tradition is dominated by the institute and classic mediums of representational art, creating something that is the opposite of that is by default original. Andreas Huyssen describes the dialectical relationship with the past as a key feature of the avant garde, which is usually perceived as being nihilistic. For Huyssen, this dialectic is how it becomes possible to distance the future with the past, and new advancements with tradition. In order to create something that is so against all the usual traditions of art, new methods of making have to be deployed, and with the advancements of photography and printed media this was made possible. 'Art can no longer exist as it used to now that photography exists' - here, Benjamin highlights the importance of the existence of photography in reshaping art - his famous work The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction from 1936 tells of the importance of technology as a way of creating works of art that no longer have the 'aura' of the original, as the work is mass produced and circulated. This circulation helps to remove the work of art from the institute. giving it more exposure to a general public rather than an elite few. This was an important part of the avant garde, as gaining public awareness bought art into life and life into art, a pivotal aim of the European movements.

As well as using mechanical reproduction in their art making process, print media was used as a means of circulated manifestos created by the movements. In 1909, Le Figaro, a leading French newspaper, published F.T Marinetti's futurist manifesto, a document that took the form of a political manifesto, outlining the aims of the Futurist movement. Krauss describes the Futurists as being an example of her idea of originality in the avant-garde, as their work and ideals were born out of nothing that came before them, and instead had a direct link with technology and breaking with traditional Italian art. During the Futurist movement, some 400 manifestos were written, ranging from sculpture through to food. Their manifestos are a prime example of how the avant garde wanted to bring art into life and life into art, with a genuine belief that art can change the conciousness of society. This belief fuelled almost all of the European avant garde movements, and is a main reason as to why Peter Burger believes the historic avant gardes failed.

When Constructivism and Suprematism were shunned by Stalin in 1934 in favour of Social Realism, or Dada, Bauhaus and New Objectivity were pushed aside after Hitler's rise to power in 1933, as well as Surrealism also falling during this time due to German occupation, it seems that the avant gardes desire to change society through art wasn't achieved.

The avant garde has been hotly debated over by critics during the last century, with many of them have different opinions on its impact and influences. Whilst Rosalind Krauss believes originality to be at the centre of the avant garde, T.J Clark counters this stating that if originality was at the heart of the practice then, the repetitive nature of their works negates the concept. This 'originality' is born out of a political and social desire to go against tradition, and when your tradition is dominated by the institute and classic mediums of representational art, creating something that is the opposite of that is by default original. Andreas Huyssen describes the dialectical relationship with the past as a key feature of the avant garde, which is usually perceived as being nihilistic. For Huyssen, this dialectic is how it becomes possible to distance the future with the past, and new advancements with tradition. In order to create something that is so against all the usual traditions of art, new methods of making have to be deployed, and with the advancements of photography and printed media this was made possible. 'Art can no longer exist as it used to now that photography exists' - here, Benjamin highlights the importance of the existence of photography in reshaping art - his famous work The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction from 1936 tells of the importance of technology as a way of creating works of art that no longer have the 'aura' of the original, as the work is mass produced and circulated. This circulation helps to remove the work of art from the institute. giving it more exposure to a general public rather than an elite few. This was an important part of the avant garde, as gaining public awareness bought art into life and life into art, a pivotal aim of the European movements.

As well as using mechanical reproduction in their art making process, print media was used as a means of circulated manifestos created by the movements. In 1909, Le Figaro, a leading French newspaper, published F.T Marinetti's futurist manifesto, a document that took the form of a political manifesto, outlining the aims of the Futurist movement. Krauss describes the Futurists as being an example of her idea of originality in the avant-garde, as their work and ideals were born out of nothing that came before them, and instead had a direct link with technology and breaking with traditional Italian art. During the Futurist movement, some 400 manifestos were written, ranging from sculpture through to food. Their manifestos are a prime example of how the avant garde wanted to bring art into life and life into art, with a genuine belief that art can change the conciousness of society. This belief fuelled almost all of the European avant garde movements, and is a main reason as to why Peter Burger believes the historic avant gardes failed.

When Constructivism and Suprematism were shunned by Stalin in 1934 in favour of Social Realism, or Dada, Bauhaus and New Objectivity were pushed aside after Hitler's rise to power in 1933, as well as Surrealism also falling during this time due to German occupation, it seems that the avant gardes desire to change society through art wasn't achieved.

Sunday, 19 April 2015

#revision - ITALIAN PHOTOGRAPHY

Photography is an important part of any avant-garde movement, as it shows the inclusion of new technologies and new modes of seeing, whilst also changing the role of the artist from one who creates on a canvas or with a sculptural material to one that captures life through a lens.

Anton Bragaglia started to use chronophotography to create images that showed photo dynamism during the early 20th century, which became important for the Futurists and their fascination with speed. Photodynamism recorded the movement of a certain object or person over a specific amount of time, and is more an image of speed and movement rather than subject matter. The Smoker from 1911 tracts the slow and leisurely movement of a seated smoker, the lit match creating bright streaks across the image. As the movements create multiple images and distorts somwhat, the feeling of speed and movement is captured perfectly. Futurist painting grew out of Bragaglia's photography, trying to emulate the speed of auto mobiles. Balla's The Car Has Passed from 1913 is a prime example of photography's influence. The fragmentation of the scene and long, jagged, visceral strokes emulate the movement of the already past car, demonstrating its speed and paintings inability to keep up with the evolving speed of cars.

Photography was also adopted as a medium for politically engaged works during the 1930's, borrowing from the Surrealist and Dada's use of photo montage and photography as a political weapon against capitalism and fascism. However, these political tendencies were changed when adopted by Italian photography,and put to use to promote rather than negate the fascist government. Bruno Munari used the photo montage aesthetic in his 1934 cover for the Magazine of Fascist Aviation, where the plane one the cover is created from a montage of different images of Italian modernism such as architecture. This photo montage is clearly put to use as promoting the Fascist party and takes on the form of a 'political weapon' in much the same way that we have come to known inter-war photography.

After the war, photography began to be influenced by photojournalism, neo-realist images and the reconstruction of Italy. It also became a medium that faced challenges of being either artistic or documentary. Franco Pinna stated that 'life is meaningless until you find a story' - for him, photography had a duty as a close to nature medium to have a story and document life. For most of his photographs he assigns text to go alongside, to give the viewer an immersive experience. Maddelena La Roca from 1952 shows an astute figure and is very clearly influenced by photojounalism, which aims to capture people and places. Contrastingly, Guiseppe Cavalli believes that photography has a right to be artistic, which means a distancing from reality. In a photo Untitled, feathers are placed on a surface and photographed, their soft amorphous forms seeming at first glance unrecognisable, with further looking allowing the viewer to finally understand. Cavalli seems to take a strong influence from the photography of the Surrealists who made strange and deflected reality.

Images to use:

#revision - ARTE POVERA AND POLITICS

A multitude of themes are touched on in Arte Povera, but one of the most contextually relevant themes to the time was politics. 'We are already in the midst of a guerilla war' ends Celant in his 1967 manifesto, hinting both to the war in Vietnam as well as the war against traditional notions of artistic practice. The war in Vietnam and America's involvement was an important influence into the student protests that were occurring in Italy during the 1960's, as well as art that was being produced at the time. Not only was there a war in Asia, but terrorism in Italy began to occur, with the leader of the Christian Party being assassinated. All of these contextual factors are reasons why Celant wanted artists to be 'guerilla warriors' and to bring art into life and life into art.

Emilio Prini's USA USA from 1969 consisted of a tape that recorded its own sound endlessly until the recorder itself broke. This is symbolic of the endless consumerist culture that came to define America, and the play on words in the title 'USA USA' (usa meaning uses in Italian) shows an almost bitterness to the way the USA treats the rest of the world. These negative feelings towards America that many Italian's had after the war were pushed further when the Vietnam war began.

Pino Pascali created realistic looking artillery out of scraps that he found, re-using discarded material that is born out of consumerism. These guns and weapons feel extremely realistic, but Pascali himself enjoyed the fact that they played with real and artificial.

Images to use:

Emilio Prini's USA USA from 1969 consisted of a tape that recorded its own sound endlessly until the recorder itself broke. This is symbolic of the endless consumerist culture that came to define America, and the play on words in the title 'USA USA' (usa meaning uses in Italian) shows an almost bitterness to the way the USA treats the rest of the world. These negative feelings towards America that many Italian's had after the war were pushed further when the Vietnam war began.

Pino Pascali created realistic looking artillery out of scraps that he found, re-using discarded material that is born out of consumerism. These guns and weapons feel extremely realistic, but Pascali himself enjoyed the fact that they played with real and artificial.

Images to use:

#revision - ARTE POVERA AND THE EVERYDAY

'The commonplace has entered the sphere of art' states Germano Celant in his Arte Povera manifesto from 1967. Many of the artists during this time focused their attention on bringing art into life and life into art. By dealing with everyday materials, subject matter and actively trying to remove artistic stereotypes, artists such as Pistoletto and Fabro attempt to capture the everyday.

Notions of the 'stereotypical artist' consisted of having a 'signature style', which is a trait that the artists during Arte Povera tried to stray away from. Celant envisaged Arte Povera as straying away from 'the oppressive and cultural system based on consumerism and tradition' and is a key reason why he theorised the use of 'poor' materials in stark contrast to that of Minimalism and American consumer culture. By making art that doesn't fit into a set 'theme' that an artist is necessitated to produce, the artist is then free from capitalist ties to the art market. However, as Pascali ironically points out, the idea of deciding to 'discard what is out of date and create novelty' is exactly the same ideas used by consumerist industry, who constantly challenge and evolve their own products to make them more marketable. This is just one of few flaws highlighted by Alex Potts in his text Disencumbered Objects, where he challenges the idea that any object can be truly disencumbered from any notions.

It is clear that these artists wanted to change the way that the world saw art, and to do so they decided to move off the canvas and into sculpture forms made from seemingly everyday materials. Boetti claims that some of 'the best moments in Arte Povera were hardware shop moments', highlighting here the use of everyday and easily attainable materials, again challenging the role of the artist. Pistoletto deals with this in his work Quandro de Pranzo from 1965, where he constructs two chairs facing one another over a table, with the whole situation framed by an outer square. Uncanny of everyday objects and activities, the frame acts as a claustrophobic barrier between those sitting in the chairs and the outside world. Pistoletto's engagement with the everyday also expanded to his work with mirrors, which placed an image of a individual on a mirrored surface, making their background surrounding interchangeable dependent on where the work was shown. On seeing your reflection in the mirror, you are put into a situation where you are unfamiliar with the individual next to you and the surroundings that you are in. This further isolates both the viewer and the image. Pistoletto's work seems to directly deal with the isolating effects of society as opposed to everyday routine and the home, which is the basis of some of Fabro's work.

Pavimiento from 1967 consists of newspapers being laid on the floor in the gallery space, reminiscent of when newspaper is used to cover a newly cleaned floor in the home. Newspapers contain the everyday happenings in the world, and to have them seemingly discarded on the floor shows the ephemeral of both newspapers themselves and the stories they contain. It seems that both Fabro and Pistoletto are in some ways critical of the everyday that has come to be part of modern life.

Images to use:

Notions of the 'stereotypical artist' consisted of having a 'signature style', which is a trait that the artists during Arte Povera tried to stray away from. Celant envisaged Arte Povera as straying away from 'the oppressive and cultural system based on consumerism and tradition' and is a key reason why he theorised the use of 'poor' materials in stark contrast to that of Minimalism and American consumer culture. By making art that doesn't fit into a set 'theme' that an artist is necessitated to produce, the artist is then free from capitalist ties to the art market. However, as Pascali ironically points out, the idea of deciding to 'discard what is out of date and create novelty' is exactly the same ideas used by consumerist industry, who constantly challenge and evolve their own products to make them more marketable. This is just one of few flaws highlighted by Alex Potts in his text Disencumbered Objects, where he challenges the idea that any object can be truly disencumbered from any notions.

It is clear that these artists wanted to change the way that the world saw art, and to do so they decided to move off the canvas and into sculpture forms made from seemingly everyday materials. Boetti claims that some of 'the best moments in Arte Povera were hardware shop moments', highlighting here the use of everyday and easily attainable materials, again challenging the role of the artist. Pistoletto deals with this in his work Quandro de Pranzo from 1965, where he constructs two chairs facing one another over a table, with the whole situation framed by an outer square. Uncanny of everyday objects and activities, the frame acts as a claustrophobic barrier between those sitting in the chairs and the outside world. Pistoletto's engagement with the everyday also expanded to his work with mirrors, which placed an image of a individual on a mirrored surface, making their background surrounding interchangeable dependent on where the work was shown. On seeing your reflection in the mirror, you are put into a situation where you are unfamiliar with the individual next to you and the surroundings that you are in. This further isolates both the viewer and the image. Pistoletto's work seems to directly deal with the isolating effects of society as opposed to everyday routine and the home, which is the basis of some of Fabro's work.

Pavimiento from 1967 consists of newspapers being laid on the floor in the gallery space, reminiscent of when newspaper is used to cover a newly cleaned floor in the home. Newspapers contain the everyday happenings in the world, and to have them seemingly discarded on the floor shows the ephemeral of both newspapers themselves and the stories they contain. It seems that both Fabro and Pistoletto are in some ways critical of the everyday that has come to be part of modern life.

Images to use:

#revision - ARTE POVERA AND NATURE

As Art Povera is such a large topic to cover, I am going to attempt to do it thematically in order to be able to cover as much as possible. In this post, I will focus on Arte Povera's relationship with the nature and environments. Germano Celant wrote of this engagement with nature in his 1969 book Arte Povera, where he states 'animals, vegetables and minerals take part in the world of art', emphasising how the materiality of work is changing to use these typically 'poor' and easy attainable materials.

Contextually, the 1960's in Italy were a time of rapid urbanisation and industrialisation post-economic miracle. Cities began expanding rapidly and the natural landscape started to diminish on the peripheries. Artists such as Pino Pascali, Guiseppe Penone and Jannis Kounellis, among many others, play with the idea of the environment and environments, and do so through the materiality and subject matter of their work. For Pascali, creating artificial natural such as his Bristle Worms from 1968 plays with the idea of nature and artifice, as he is using an artificial material to create a natural form, which he then places outside in the natural environment. Penone also works outside of the gallery space, but does so in a more natural way and is concerned with humans imprint on nature as opposed to the play between natural/artifice. His Alpi Marittime's from the same year consist of metal casts of the artists hand wrapped around the trunks of sapling trees - when these grow, they form around the cast and are evident of humans affect on nature, consistently adapting to the presence of society.

Kounellis is also influenced by nature, but instead of working outside, he brings nature into the gallery space. In 1967, he bought a colourful parrot into the gallery space at L'Attico, where it was free to fly around the gallery space. The parrot created a tropical environment in the gallery space, but also played with the idea of confinement and captivity. A year later in 1968, 12 horses were bought into L'Attico and exhibited, using the new gallery space as a barn. Smells and sounds alongside visual were engaged, and the exhibition was seen as 'an organised controlled presentation of nature', which says something about the fact the horses were tied to the walls. Whilst nature was being presented, it was a restricted version that is symbolic to the way the cityscapes urbanise nature.

Images to use:

Thursday, 16 April 2015

#revision - GALLIZIO AND INDUSTRIAL PAINTING

Where the neo avant-garde Italian artist Manzoni thought satirically and playfully of consumerist and capitalist society, Guiseppe Pinot-Gallizio thought more deeply and reactionary. After meeting avid Marxist Guy Debord and the International Situationist's, Gallizio became more involved in a Marixst and social type of art making reminiscent of that seen in countries like Russia or Germany during the historic avant-gardes. Through a process of mechanised and collective making, Gallizio's Industrial Paintings were born and aimed to remove themselves from the gallery space and be widely available to the public.

The process of making become important if not absolutely pivotal to the artwork, with the emphasis taken away from the artists hand and put onto that of the machine. Created on a rickety table with rollers covered in varying substances, each roll of mass produced but unique, which Frances Stracey sees as not regressing to the 'unique touch of the artist', but instead emphasising that all that is mechanically produced is not necessarily identical and void of personality, as a commodity culture would have us believe. Further benefits of having a machine create the huge lengths of these paintings is that it can be a cumulative human effort from many people, and therefore the mass of painting produced creates a surplus value that can split between all those involved, creating a social type of art form. The rolls of painting can be cut into desired sizes instead of being one revered art object that is available for only one, privileged person. Furthermore, the traditional notion of the artwork living in the gallery space is subverting, with a preference to existing in the urban streets.

Images to use:

The process of making become important if not absolutely pivotal to the artwork, with the emphasis taken away from the artists hand and put onto that of the machine. Created on a rickety table with rollers covered in varying substances, each roll of mass produced but unique, which Frances Stracey sees as not regressing to the 'unique touch of the artist', but instead emphasising that all that is mechanically produced is not necessarily identical and void of personality, as a commodity culture would have us believe. Further benefits of having a machine create the huge lengths of these paintings is that it can be a cumulative human effort from many people, and therefore the mass of painting produced creates a surplus value that can split between all those involved, creating a social type of art form. The rolls of painting can be cut into desired sizes instead of being one revered art object that is available for only one, privileged person. Furthermore, the traditional notion of the artwork living in the gallery space is subverting, with a preference to existing in the urban streets.

Images to use:

Labels:

alma,

debord,

gallizio,

industrial,

marx,

painting,

revision,

social art

#revision - ITALIAN NEO-AVANTGARDE

Whilst I have covered the neo-avant garde in a previous post, I would like to think more specifically about the Italian neo-avant garde artists, namely Lucio Fontana, Alberto Burri and Piero Manzoni. Of course Peter Burger's Theory of the Avant-Garde comments on the failings of the neo-avant gardes, stating that any revolutionary tendencies are replaced with repetition and institutionalisation, I would like to this about the Italian artists as reacting to their post-war status in Italy. Whilst they all do in some ways deal with the idea of the 'monochrome', it is less so in a repetitive and reductive way as seen the American East coast artists, and more so in a culturally significant way.

For artists like Burri and Fontana the dialectic relationship of damage and repair is evident in their works, and for Jaimey Hamilton, this can be reminiscent of the damage caused by the war, particularly in the case of Burri. Hid stitched burlap sacks are overlaying red painting or globulous plastic surfaces which have an uncanny resemblance to the injured body. Whilst Hamilton appreciates that Burri himself has never admitted to any of these suggestions that have been made about his work, he employs a Freudian theory of repetition through repression to enforce his argument, stating that the dynamic of damage and notions of war are undeniable. Instead of simply rethinking the monochromatic and reductive tropes of the historic avant-garde as Burger would suggest, Burri is instead creating work out of a culturally situation and time.

This type of damage is reflected in the work of Fontana too, however with less conviction and explicitness than in Burri. Fontana's Spatial Concepts from the 1950's deal with the gestural movements, from stabbing to slicing, which play with the stability of the surface. Greenberg believes that the surface of the work in an important part of modernist painting, but Fontana almost violates this by destroying this plane. Fontana believed that the something new had to be created to replace the traditions of painting and sculpture, and to do this he creates through his destruction in an ironically similar way to the nihilism and utopian dialectic that runs deep in the historic avant-garde.

Alongside the dynamic of damage, there is also a fascination with the commodity and it's new found place in society, especially within the art market. For Manzoni, this was a key theme that ran through his work. As noted before, he had his Acromes, which dealt with the reduction of the last pictorial element that runs through most monochromes, colour, and deals with repetitions and differences within them. Some of his other work was more heavily based on consumer culture, and was acted out in a performative way. In a 70 minute performance participation piece, Manzoni hard boiled eggs and signed the shell with his thumb. These eggs were then given out to viewers and eaten, literally consuming his art works and the 'aura' of the artist. In the crude Artist's Shit, tins of what is meant to be Manzoni's faeces is placed in tins and sold for the weight of gold at the time. The packaging was printed in different languages so that it was a true global mass consumed commodity, and it is clear that these gestural and performative works question the ideals and values of the art world.

The performance aspect of all three of these artists work is just one way that they are united. Black and white photographs by Ugo Mulas heighten the drama and narrate the story of creation that these works go through.

Images to use:

For artists like Burri and Fontana the dialectic relationship of damage and repair is evident in their works, and for Jaimey Hamilton, this can be reminiscent of the damage caused by the war, particularly in the case of Burri. Hid stitched burlap sacks are overlaying red painting or globulous plastic surfaces which have an uncanny resemblance to the injured body. Whilst Hamilton appreciates that Burri himself has never admitted to any of these suggestions that have been made about his work, he employs a Freudian theory of repetition through repression to enforce his argument, stating that the dynamic of damage and notions of war are undeniable. Instead of simply rethinking the monochromatic and reductive tropes of the historic avant-garde as Burger would suggest, Burri is instead creating work out of a culturally situation and time.

This type of damage is reflected in the work of Fontana too, however with less conviction and explicitness than in Burri. Fontana's Spatial Concepts from the 1950's deal with the gestural movements, from stabbing to slicing, which play with the stability of the surface. Greenberg believes that the surface of the work in an important part of modernist painting, but Fontana almost violates this by destroying this plane. Fontana believed that the something new had to be created to replace the traditions of painting and sculpture, and to do this he creates through his destruction in an ironically similar way to the nihilism and utopian dialectic that runs deep in the historic avant-garde.

Alongside the dynamic of damage, there is also a fascination with the commodity and it's new found place in society, especially within the art market. For Manzoni, this was a key theme that ran through his work. As noted before, he had his Acromes, which dealt with the reduction of the last pictorial element that runs through most monochromes, colour, and deals with repetitions and differences within them. Some of his other work was more heavily based on consumer culture, and was acted out in a performative way. In a 70 minute performance participation piece, Manzoni hard boiled eggs and signed the shell with his thumb. These eggs were then given out to viewers and eaten, literally consuming his art works and the 'aura' of the artist. In the crude Artist's Shit, tins of what is meant to be Manzoni's faeces is placed in tins and sold for the weight of gold at the time. The packaging was printed in different languages so that it was a true global mass consumed commodity, and it is clear that these gestural and performative works question the ideals and values of the art world.

The performance aspect of all three of these artists work is just one way that they are united. Black and white photographs by Ugo Mulas heighten the drama and narrate the story of creation that these works go through.

Images to use:

#revision - NEO-REALIST ITALIAN FILM

As part of my Italian Avant-garde course this year, we did a week on post-war Italian neo-realist film, which opened me up to a whole new medium of art making that can be as symbolically rich as any painting or sculpture. With a focus on Rome, Open City from 1945 by Roberto Rossellini, Bicycle Theives by Vitorria Di Sica from 1948 and L'eclisse from 1962 by Michaelangelo Antonio, I will consider the changing notions of the city and its periphery, as well as the rhetoric potential of sites and buildings within film.

The EUR on the outskirts of Rome was built as a fascist cultural marker for the 20 years of power that Mussolini had achieved, as well as marking the hopeful future of fascism within Italy. Placed towards the Mediterranean Basin that Mussolini hoped to one day be in control of, the EUR would have been a powerful and symbolic place had it been completed prior to WWII. Unfortunately, the neo-classical building was left abandoned, and after the collapse of the Italian Fascist regime in 1943, the building had a ghostly and empty presence, and the EUR came to symbolise the damaging past. It is this symbolism that John Rhodes uses when speaking about Rossellini's film Rome, Open City, which is a work highly critical of fascism. Rhodes highlights how the pivotal and devastating scene of leading lady Pina's death is closely followed by a scoping view of the desolate EUR landscape, with Rossellini believing that buildings and places hold strong rhetoric values. Whilst this may be the case, and made for highly emotive and charged scenes in the film, Rhodes argues that places are static and values are place upon them from the outside, a case that is acutely clear with the EUR.

Rome, Open City depicts the EUR as a ghostly reminder of a fascist past, however if we compare this to its interpretation in Antonio's L'eclisse, shot on location less than twenty years later, the change is significant. After the economic miracle in Italy, the EUR became a sight for suburban development, where many middle class families moved to live. Instead of holding onto the ghosts of its past, the EUR became a centre of capitalist consumer culture, or as Antonio calls it, 'the world the bourgeoisie'. At the end of L'eclisse, fragmented shots of urban life flick past one another to a silent score of music, each shot dragging, emphasising the mundanity of life but adding an anxious undertone to the film. The anxiousness is furthered with the onset of the nuclear bomb and fear of losing the economic security that they have. Antonio uses these film medium techniques to create a tense environment and the underlying issues and anxieties that lie beneath the pleasant bourgeoisie exterior.

Both of these films have a dominant focus on the EUR and its changing symbolism, however they also actively focus on the periphery of the city. After being war torn, Rome was under stress to deal with the poverty that the war bought, and inner-city housing projects were developed under the Marshall Plan. In Bicycle Thieves from 1948, the poverty of this region is highlighted, showing ramshackle and unfinished buildings. There are critical undertones towards fascism and war and the devastation that it bought.

Film can be a powerful way of creating relationships with politics or revolutionary change, especially when loaded with symbolism. The periphery of Rome was a changing place post-war, and as the final scene of Rome, Open City suggests, in which we see the cast walking towards the city and St Peter's cathedral, the city and religion seem to be the salvaging hopes.

Images to use:

The EUR on the outskirts of Rome was built as a fascist cultural marker for the 20 years of power that Mussolini had achieved, as well as marking the hopeful future of fascism within Italy. Placed towards the Mediterranean Basin that Mussolini hoped to one day be in control of, the EUR would have been a powerful and symbolic place had it been completed prior to WWII. Unfortunately, the neo-classical building was left abandoned, and after the collapse of the Italian Fascist regime in 1943, the building had a ghostly and empty presence, and the EUR came to symbolise the damaging past. It is this symbolism that John Rhodes uses when speaking about Rossellini's film Rome, Open City, which is a work highly critical of fascism. Rhodes highlights how the pivotal and devastating scene of leading lady Pina's death is closely followed by a scoping view of the desolate EUR landscape, with Rossellini believing that buildings and places hold strong rhetoric values. Whilst this may be the case, and made for highly emotive and charged scenes in the film, Rhodes argues that places are static and values are place upon them from the outside, a case that is acutely clear with the EUR.

Rome, Open City depicts the EUR as a ghostly reminder of a fascist past, however if we compare this to its interpretation in Antonio's L'eclisse, shot on location less than twenty years later, the change is significant. After the economic miracle in Italy, the EUR became a sight for suburban development, where many middle class families moved to live. Instead of holding onto the ghosts of its past, the EUR became a centre of capitalist consumer culture, or as Antonio calls it, 'the world the bourgeoisie'. At the end of L'eclisse, fragmented shots of urban life flick past one another to a silent score of music, each shot dragging, emphasising the mundanity of life but adding an anxious undertone to the film. The anxiousness is furthered with the onset of the nuclear bomb and fear of losing the economic security that they have. Antonio uses these film medium techniques to create a tense environment and the underlying issues and anxieties that lie beneath the pleasant bourgeoisie exterior.

Both of these films have a dominant focus on the EUR and its changing symbolism, however they also actively focus on the periphery of the city. After being war torn, Rome was under stress to deal with the poverty that the war bought, and inner-city housing projects were developed under the Marshall Plan. In Bicycle Thieves from 1948, the poverty of this region is highlighted, showing ramshackle and unfinished buildings. There are critical undertones towards fascism and war and the devastation that it bought.

Film can be a powerful way of creating relationships with politics or revolutionary change, especially when loaded with symbolism. The periphery of Rome was a changing place post-war, and as the final scene of Rome, Open City suggests, in which we see the cast walking towards the city and St Peter's cathedral, the city and religion seem to be the salvaging hopes.

Images to use:

Labels:

antonio,

di seca,

EUR,

film,

italian,

neo-realist,

open city,

post-war,

revision,

rossellini

#revision - NEOCONCRETISM

Neo-conrete art in Brazil during the 1950's and 60's was reassurance of the fact that the re-shaping of art was not just a European and American movement, but also a global one. Concrete art was influences by the constructivists of Russia, and neo-concrete was a strain of the same movement that focused on putting more colour and sensuality into the movement. I am going to focus on the relationship that neo-concretist's formed with the body through their art, particularly looking at the work of Lygia Clark and Helio Oticica.

The manifesto for neo-concretism featured the names of influential artists such as Mondrian and Malevich and their focus on reduction and geometry, and the artists in Brazil used these as influences in their movement, but aimed to do so in a way that was sensual and engaged with the body, but still had purity in non-representation forms. Both Clark and Oticica started their neo-concrete careers creating geometric and monochromic forms, with Clark's being on a match box scale and Oticica's being larger. Both could be moved and engaged with and both honoured the constructivist ideals of geometric purity. Out of these objects, Clark and Oticica developed individual styles that involved viewer participation.

Clark turned to psychotherapy in 1975 and was interested in the mind, and her works speaks volumes for this interest. Her 'creatures', which were geometric sculptures that could be moved in a way that was similar to an organic being, necessitated viewers as being vital for their existence. Guy Brett writes of these objects as only being meaningful when they are in participation with a viewer, and that each meaning and understanding of the object is assigned through a personal and intimate experience with the object. This type of 'intimacy' is also seen in Air and Stone from 1966, where cheap materials such as a plastic bag filled with air and a stone are utilised, and the bag is gently pushed and let go of so that the stone rises and falls, synonymous with the breathing pattern of a human and used in a therapeutic way. Clark's deliberate use of cheap and attainable materials come out of her desire to create work that 'anyone with my [Clark's] roots can make'. For her, the constructivist tendencies of creating a social art have not died.

Oticica also created works that demand a viewers engagement to be validated and understood, and did so by creating his Paragoles which were colourful creations made of material that were created to be worn. Ideally they were to be worn when dancing to the samba, creating a sensual explosion of colour and unifying a group of people.

Images to use:

The manifesto for neo-concretism featured the names of influential artists such as Mondrian and Malevich and their focus on reduction and geometry, and the artists in Brazil used these as influences in their movement, but aimed to do so in a way that was sensual and engaged with the body, but still had purity in non-representation forms. Both Clark and Oticica started their neo-concrete careers creating geometric and monochromic forms, with Clark's being on a match box scale and Oticica's being larger. Both could be moved and engaged with and both honoured the constructivist ideals of geometric purity. Out of these objects, Clark and Oticica developed individual styles that involved viewer participation.

Clark turned to psychotherapy in 1975 and was interested in the mind, and her works speaks volumes for this interest. Her 'creatures', which were geometric sculptures that could be moved in a way that was similar to an organic being, necessitated viewers as being vital for their existence. Guy Brett writes of these objects as only being meaningful when they are in participation with a viewer, and that each meaning and understanding of the object is assigned through a personal and intimate experience with the object. This type of 'intimacy' is also seen in Air and Stone from 1966, where cheap materials such as a plastic bag filled with air and a stone are utilised, and the bag is gently pushed and let go of so that the stone rises and falls, synonymous with the breathing pattern of a human and used in a therapeutic way. Clark's deliberate use of cheap and attainable materials come out of her desire to create work that 'anyone with my [Clark's] roots can make'. For her, the constructivist tendencies of creating a social art have not died.

Oticica also created works that demand a viewers engagement to be validated and understood, and did so by creating his Paragoles which were colourful creations made of material that were created to be worn. Ideally they were to be worn when dancing to the samba, creating a sensual explosion of colour and unifying a group of people.

Images to use:

#revision - PROCESS ART

Today I am going to look at 'Process Art', focusing on the works of Eva Hesse and materials that keep evolving even after their creation, and what this means for their display and longevity.

'Process Art' is a type of art that focuses on the process of making and evidence of making, with the end product seemingly not as important. It seems like a strain of conceptual art, in which the end product means less than the idea, but becomes a much more physical rather than metaphysical way of creation, where the appearance of the end product is determined by the process instead of the idea, making the object a pivotal part of the work. The process of making is not hidden away, and even becomes the subject of the work. As Greenberg says, the role of modernism in art means that art can be about itself, with no defined representational subject.

Eva Hesse is renowned for her work with latex, using it for it's experimental properties, it's positioning in the realm between painting and sculpture and it's bodily properties. Using latex that can be painting in sheets, Hesse created Augment in 1968, layers of latex partially stacked over one another and placed on the floor. These rough edged layers do not shy away from their process of creation, but what is most important about latex is the ongoing process it goes through in it's life. Starting life as a pale, flexible and rubbery surface reminiscent of flesh, through humidity and oxidisation the latex begins to harden, yellow and eventually crack away, slowly but surely disappearing. This ongoing process can be seen as being a trope in Hesse's work, who justifies the change by saying 'art doesn't last. Life doesn't last. It doesn't matter'. Whilst this may be the case for the artist, it has been a substantial problem for museums and galleries who show Hesse's work.

At the 2013 Venice Biennial, there was a re-staging of the 1969 show When Attitudes Become Form, curated at the time by German Celant. Augment was one of the works to feature in the original show, but due to the process of change that the work had undertaken over the last 30 years, the work was damaged and cracked and the top layers, and the sheets had to be changed around and moved in order to re-exhibit the work. Thankfully the lower layers had little oxidisation deterioration and could be utilised. It is this type of 'process' that vex's museums today, but captures the artists intent perfectly.

Process art can also link directly the post-studio art that was spoken about in the last post. Keith Sonnier's Red Flocked Wall also utilises latex, and is created by painting it directly onto the wall and the peeling the lower part off so that the latex covering hangs. The process of making is evident in this work, and as it is not made in the studio it is original to each gallery space it is presented in. For Mel Bochner in 1 language is not opaque, the same process occurs but this time with paint, each time the drips are in different places and the process of making is transparent.

Images to use:

Wednesday, 15 April 2015

#revision - POST STUDIO AND CONCEPTUAL ART

Conceptual and post-studio art are terms that can fit a wide range of art types after the 1960's, including land art, performance or more classic mediums such as painting and sculpture. However, it is contested what is meant by the 'post-studio', as the notions of what a studio actually is have come into question. In his influential writing on the studio, Buren posits that the studio is the place where the work is created, and once it leaves this place it loses its aura and context. Buren creates the majority of his art on site so that this aura is not lost, and the work is made to belong where it is situated. But does a studio necessarily mean a room or building in which things are hand-crafted? The traditional notions of the studio are where the solitary artists creates masterpieces in private, and photographs and paintings of the studio have confirmed this mythical identity. The idea of a studio is changing now - if we look at a photograph of Duchamp's 'studio', we see a collection of readymades assorted in an orderly exhibition style manner. What kind of studio produces a readymade? These objects have already existed before entering the 'studio' - we are faced with a non-traditional portrayal of the studio that challenges our preconceived ideas about creation. Maybe the studio has now evolved to a point where instead of a physical place, a mental place can be seen as the origin of the art work. In conceptual art, it is usually the idea that drives the work as opposed to the object itself, and in this changing notion of what constitutes the 'art', what constitutes the 'studio' is also questions.

'The idea becomes the machine that makes the art' - Sol Le Witt summarises that ideas in conceptual art become the important factor that define what makes a certain object or image 'art'. In his writings on contemporary art, Le Witt states that often the object in incidental to the idea, but it is not the agenda of the artist to explain in any depth the idea behind the work. Here, we are left with a confusing made of viewing, where the object is not the work but the idea is not clear. This is the basis for much conceptual work of the time. On Kuwara's Date Paintings seem relatively mundane and repetitive from the outside, with their monochrome backgrounds and their block lettering, and this is partially down to their display as well as the artists anonymity. When these paintings are displayed it is usually hung on a wall without their sub-titles that Kuwara has assigned them, or the newspaper page that they come boxed with, which aligns itself with Buren's theory that paintings lose their aura when in a gallery, as a gallery space does not personalise itself to a work. When the sub-titles and the newspaper are displayed alongside the work, we see a whole different angle - the titles are morbid and consciously aware of the war and death that happens in the world, especially the aggressive happenings in Asia and Vietnam during the 1960's. What is intended from these titles is little known, as the artists own privacy leaves little writings about the topic. Whether it is a comment on the numbing nature of the media on violence, or the process of time and forgetting is unknown.

Whilst Kuwara had a studio, many of his works were done when he was away, and therefore created outside of the studio, fuelled by the idea as Le Witt states. For some artists, including Buren, work outside of the studio is the most valid, as it is created for the space that it lives in. Artists like Robert Smithson and his Sprial Jetty or Mel Bochner and his 1 Language is not transparent create work that lives in the place it is made, and can be recreated if it needs to moved, which is particularly true of Bochner. With his piece, there is a no set 'orginal' piece, which further subverts our notions of what art is meant to be, and reduces that value that the market can put on it.

Images to use:

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)