Wednesday, 15 April 2015

#revision - NEOAVANTGARDE/MONOCROME

Using Peter Burger's and Benjamin Buchloh's opposing ideas about the neo-avant garde, I will explore why the monochrome has reappeared as an artistic practice and the various ways that the monochrome has been utilised by artists.

Peter Burger's Theory of the Avant-Garde dismisses the neo-avant-garde has being merely a repetitive form of the historic avant-garde that is void of the original, revolutionary tendencies of the earlier movement. Due to the failings of the historic avant-garde, Burger sees no possible way that by repeating their actions anything meaningful is bought around, and the artworks merely become institutionalised. We need only look at the works of Malevich and Rodchenko that occurred in the last post to see that the monochrome was a break from traditional artistic values and art practice in general. For Rodchenko in his Pure Colours of 1921, all preconceived artistic ideals were removed from the colours - no longer were these representational or emotive tools, they were simply used for their materiality on the canvas. These notions of material colour are reminisced in the work of Robert Rauschenberg, particularly his Black Paintings from 1951, where the texture and reflectivity of the paint and the materials placed under the paint were pivotal to the work, and not any of the emotive associations that are normally ingrained in colour. 'Meaning belongs to people' - this quote from Rauschenberg highlights his desire to distance himself from emotion, a particularly difficult task in a time when artists like Jackon Pollock and Mark Rothko are been revered for their emotional abstract works.

Buchloh enhances Rauschenberg's idea that instead of meaning coming from the inside of the work, it is put on the work from the outside. This interpretation of the neo-avant-garde goes against the theory of Burger, where he believes the artists are trying to assimilate the intentions of the historic avant-garde. Buchloh believes that the meanings put onto monochromes occur from the outside, and uses Yves Klein as his key example. In the spectacle that is Klein, his monochromes are sold for varying prices depending on how much importance is put on them from the outside - there are no obvious distinctions between the canvases, all the paint is rolled on to produce flat even planes and they are exhibited together, yet they sell for different prices. In creating a spectacle, the commodity value of the works goes up, and the value of these work is decided by others.

This type of monocromy was also occurring in Italy at the time, with Piero Manzoni's Achromes being deliberately void of representation and focusing instead on the materiality of the work. 'To suggest, to express, to represent: these are not problems today' - Manzoni's thoughts seem to echo those of Rauschenberg and Buchloh, where art has long been emotive and representation. By using works of varying textures such as polystyrene, wool, fur and feathers but keeping the colour white, Manzoni is playing with materiality instead of emotive associations, as does Rauschenberg in his White Paintings - they are seen as purely reductive. Reduction was always a trope of the historic avant-garde, who used it as a shock factor. In its more modern use, we can see how Burger's theory of institutionalisation has played itself out, regardless of the meaning of the works themselves.

Images to use:

Tuesday, 14 April 2015

#revision - ABSTRACTION

For Clement Greenberg, modernism is born out of self-criticality. This self-criticality within painting picked up that since painting began, the flat surface of a painting has been seen as a pivotal part of what makes a painting a painting and which sets it apart from all the other arts. On top of this flat plane, a three dimensional image has been created, which in some ways negates the fact that it is on a flat surface, as nothing eludes to this within the image. 'Flatness alone was unique and exclusive to pictorial art'; Modernism, for Greenberg, focuses on the emphasising this plane and making use of it, doing away with figurative representation, as three-dimensionality is something shared with sculpture, and becoming autonomous through the individual use of a flat plane.

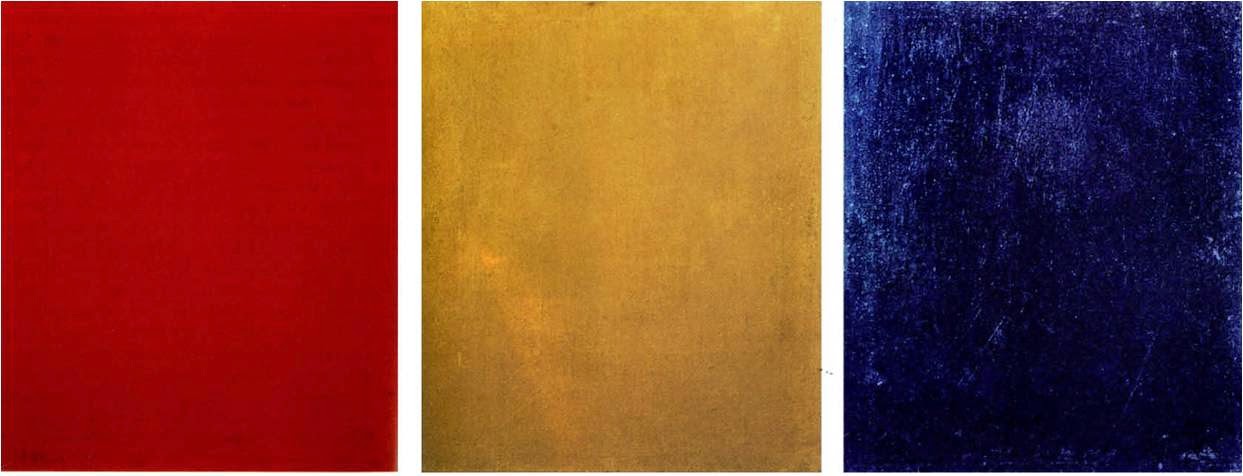

Artists like Piet Mondrian and Malevich have used abstraction as means of emphasising the surface of the work. In Russia, Malevich created his famous Black Square as a reduction of all representation and even that of colour. When representational art had become so tied up in bourgeoisie values, it was important if Russia was to succeed with a new regime to distance themselves artistically with this past. Alexander Rodchenko created the Last Painting in 1921, three monochrome panels that consisted of the primary colours red, yellow and blue. This was seen to be the 'death of painting', as it showed painting in its purest forms - the three primary colours, which make all colours, and the flatness of the three canvases. From this moment onwards, Rodchenko had a preoccupation with photography, especially after the rise of the Bolsheviks in 1917 deemed abstraction and suprematism to be disengaged with the everyday reality.

Mondrian emphasises the plane in a slightly different way. Whilst the monochromes in Russia are void of all representation, there are still some simple, pure elements of that in Mondrian's grids. Following a repetitive grid method that he used for 25 years, Mondrian created many works that follow the same repetitive technique but are infinitely different in their representation. The act of repetition, or 'systematic' art, uses repetition not to show similarities but to show differences. Mondrian's art shows that not all artistic license is lost when figurative painting is removed.

Two modern artists who have carried on the trope of abstraction are Barnett Newmann and Ellsworth Kelly. Both of these artists use monochromes to emphasis the flatness of the surface, and both loosely utilise grid formations. Newmann's One from 1948 is a monochrome (made in a series of 5, furthering the 'systematic' process of abstract art) with a single vertical line down the middle, showing it is conscious of the limits of the surface and the edges of the plane, whereas Kelly's Red/White from 1953 uses the grid in a more explicit way, with the whole canvas being in a grid formation. This formation is one of the most effective ways to play with the Freudian idea of chance, which many artists during this time are occupied with.

Images to use:

#revision - PHOTOMONTAGE

Photomontage can be neatly split by locations - Russia, Berlin and Paris. Each of these places held certain characteristics within their montage, influenced by the countries current context.

Russia and Constructivism

Constructivism was born out of a desire to have an art form that fits in with Marxist dialogue. To do so, photography was utilised for its cheapness and its reproducibility - no longer will artworks be expensive and institutionalised, they will be mechanically reproducible and circulated throughout the country. Osip Brik notes how photography is a more available artform; 'the cheapest painting is still more than the most expensive camera' - the painting art form has now become too intrinsically tied with bourgeoisie values, whereas photography is a clean break. To enforce this new social type of art, the artist's status is rethought to turn them from artist into engineer, at one with the workers. El Lissitzky's Self Portrait from 1924 uses montage to create overlays of graph paper, alphabet letters, shapes and a compass held in the artists hand overlaying the artists eye. There is a lot of rich imagery in this image that is suggestive of the dawn of a new era and the new status of the artist. The ending letters of the alphabet can be seen as nearing the end of the old regime, giving birth to a new art form that uses mechanical tools (a compass and graph paper) to create artworks. Having the artists face partially obscured by the hand emphasises the mechanical use of tools as opposed to the artistic touch of the artist, and brings him at one with the workers. In much the same way, Gustav Klutsis' 1930 photomontage of Let us fulfil the plan of the great projects uses the hand to symbolise a social and engaged art form. Here, the artist uses his own hand to symbolise the salute of the works, and this is repeated to create a mass affect. Instead of using his face or even acknowledging that this hand is his, it is left anonymous, leaving any worker who sees the photomontage to feel connected. Klutsis uses photomontage as an agitational political tool to try and reinforce the ideologies of the new Marxist government - this type of photomontage holds strong similarities to that of Berlin Dada, where political agitation was key, however the artists in Germany were typically used the new medium against the current government instead of for.

Berlin and Dada

In Germany's heavily capitalist society, many artists became influenced by a Marx and utilised photomontage as a political weapon against the current regime. Artists like John Heartfield, George Grosz and Hannah Hoch created photomontages that was heavily political and utilised techniques that they had learnt from their time in advertising before turning to art. As with Constructivism, this new art form eluded institutionalisation from its mass produced and proliferated status, making it another social movement. In Cut with the Kitchen Knife from 1919, Hoch not only makes a capitalist critique with her montage made from old discarded newspapers and abject materials, but also comments on female representation within the media. To go into Berlin Dada with any depth right here would be endless, but it is enough to say that this era of photomontage was highly politicised and its main aim was reproduction and mass movement.

Paris and Surrrealism

Not only influenced by Marx, but more explicitly by Freud, according to Rosalind Krauss, Surrealist photography falls into two distinct categories': the academic/illusionist and the autonomist/abstract. Both of these categories are heavily influenced by the Freud and his theories on dreams, the uncanny, chance and psychoanalysis. The aim of Surrealist photography seemed to be then to make strange and deflect reality. Brassi's Involuntary Sculpture series from 1910 seems to address the Freudian idea of chance whilst also making strange with its close up angle. Man Ray was also a leading figure when it came to taking images of mathematical objects in such a way that they are unrecognisable.

Images to use:

Monday, 13 April 2015

#revision - READYMADES

Topic two is the readymade. In this piece I will explore the questions that are asked with regards to the readymade, how our notions of the readymade have changing over time and how the idea of the readymade has translated into our current art climate.

When faced with the readymade, three questions spring to mind - what is the role of the artist, what is the role of the institute and in what ways is the readymade an 'artistic object'? Ever since Marcel Duchamp signed a urinal with R.Mutt in 1917, when it was quickly rejected by an art show, our idea of the readymade has been loaded with questions. These objects are not made by an artist's hand, they are instead chosen by the artists. Does this negate the object as being artistic at all? Is it a mass produced object that becomes artistic through an artist's idea or concept? Fountain was an iconoclastic object that aimed to upheave preconceived notions about the art object, artist and gallery space, if anything in a mocking way of the current bourgeoisie artistic values. This idea of 'iconoclasm' is faced when we look at how the object is represented now. Peter Burger writes in his Theory of the Avant-Garde that what was once iconoclastic and revolutionary now becomes institutionalised and canonical. When the intention of a readymade is to be iconoclastic, does this concept get broken down when the institute finally accepts the artistic authority of the object?

Joseph Kosuth states that the role of the artist is now to ask questions. Done so explicitly by Duchamp, the ideas and questions raised by the readymade have filtered into a more modern practice, one which has different idealistic notions about the readymade. Kosuth himself asks questions about readymade objects - in his Shovel piece, which is recreated in each venue (which leads us to the realisation that with a mass produced 'readymade' there is no original) the actual object, a photo of the object and a definition of the object are placed next to one another - they are all the same but different. In a gallery space, the readymade problematizes its own display. Instead of representing something in the way that a painting or a sculpture would, we are instead faced with a re-presenting of an everyday object. And if the original is lost, as in Duchamp's In Advance of a Broken Arm, a lone shovel, then the object may need to be remade. Unlike Kosuth's shovel, a new one is not used in each venue, and instead a new shovel was fabricated - this is another problem in terms of the 'concept' of the readymade. If an object has to be fabricated to the specific requirements of an object before hand, the whole idea of a readymade is diminished.

No longer are artists trying to actively disrupt the institute - they are questioning what we see every day, the consumerist culture that we live in and how we react to it and the objects we face. Jasper John's uses everyday motif's such as targets or the American flag, 'readymade' images, and uses them as the subject matter for his work. When viewing these objects that we see regularly in our everyday life, we are faced with an uncanny recognition. Taking the concept of the readymade a step further with his notion of the 'all readymade', Ellsworth Kelly creates works that take inspiration from life in much the same way as Johns. However, instead of using overly visual and recognisable motifs, we are faced with subtle snippets of window frames or bus stop signs. These 'readymade' shapes are found everywhere - very much like Duchamp's urinal. Yet whilst these objects are designed to be impassive, detached and purged of artistic discourse, Rosalind Krauss offers her Freudian influenced thoughts that something deeper may lay beneath the impassive exterie of these objects. In Freudian theory, seemingly meaningless behaviour is actually embedded in deeper meaning - following this theory, is it possible that these objects tell us more?

Images to use:

#revision - COLLAGE

To help me revise I am going to write a series of shorts about a certain topic, basically so that I can get to grasps with the basics of each subject, the critics/artists/artworks/context. By posting it on here it is encouraging me to actually do it instead of say I'm going to do it and then not...

So topic one is on cubist collage. By using the texts of Clement Greenberg and Louis Aragon, I am going to attempt to outline the defining features of collage and how this has affected modern art up until our current point. If we take the musings of Greenberg, who posits that modernism manifests itself in art that creates a relationship with the actual artwork itself rather than what is being depicted, then we can begin to pick apart the work of Picasso and Braque. These two artists had a fascination with the surface of the work, particularly in creating a definition between the surface of the canvas and the subject on top. To do so, the collage technique was developed by pasting found objects such as fabrics, newspapers, ropes or even paints mixed with sand onto the canvas, which could create shadowing or a disjunctive way of viewing the image. Using the word 'image' may be problematic here, as collage seemed less involved with the image and more involved with the process and visibility of different planes. Greenberg believes that art can be just about itself, and this is something that is exemplified through the process orientated works of both Picasso and Braque.

Louis Aragon characterises cubist collage as falling into two categories: that which focuses on the 'formal', for example that has been created around the positioning of one certain object/material, and that which focuses on the materiality, for example a textural material or something that creates a defined colour palette. These two types of collage are interchangeable in the practises of both Picasso and Braque, with Picasso taking the latter a step further when he begins constructing his cubist sculptures. These are heavily orientated around the usually found materials that they are constructed out of, and they take the separation of the surface/subject planes to a step further. These objects are now three-dimensional and sit above the surface, casting shadows in much the same way as Braque's primary work, where a nail casts a shadow across the flat plane of a canvas. This could be seen as a full circle in the development of collage, however collage has had a far further reach than just cubism, which is seen almost critically be Aragon who states that 'art has ceased to be original' as the endless borrowing of ideas continues.

Many a movement is born out of collage; dada photomontage is one of the most explicit examples, where collage takes on a political and propagandist motive and transgresses into the anti-aesthetic medium of montage. Formally it is the most reminiscent, yet other movements share attributes less obvious. Abstraction can be seen as following in the footsteps of art that is detached from social engagement, a purely aesthetic experience that sees the collapse of representation. If we take Mondrian, we see an over-emphasis of the flatness of the plane, where the surface and the subject are inextricably close yet transcending one another. It is even possible to take the notions of deskilling and the removal of the artists hand to say that the idea of the readymade grew out of cubist collage. As Max Ernst poignantly states. 'it is not the glue that makes the collage'.

Images to use:

Thursday, 2 April 2015

It's Nice That; Frida Khalo

I am loving these photographs of Frida Khalo's belongings on It's Nice That. It's eerie. Click the link to follow > Its Nice That

Forensics: The Anatomy of Crime @ Wellcome Collection

In preparation for my interview at the Wellcome Trust (aahhh!) I thought it would be a good idea to go and familiarise myself with the exhibitions that are on at the moment. Forensics: The Anatomy of Crime opened at the end of February, and I have been wanting to see it for a while. Like a lot of people, I am fascinated with crime in general, whether it be on tele, in a book or in art. It's a fascinating and complex study and something I wish I had been smart enough to get into!

The exhibition is extremely interesting, breaking the whole process from crime scene to court. It features real life case studies, gruesome fragments of body parts and organs, artists works that are influenced by forensics and a range of materials from medieval manuscripts to video presentations. It is an engaging exhibition that is definitely work taking the time to explore and read every bit of detail. The first room, The Crime Scene, was particularly interesting with an area focused on Jack he Ripper, another on crime photography and various other things, including a vial of gross blowfly maggots from a corpse. The grossness continued into the next room, the Morgue, in which the interesting French history of the morgue was laid out and fragments of dissected and injured organs sat in cases. I even stood through the video of the mortician talking about her role which was mega interesting.

As well as the actual knowledge that was abundant in the exhibition, I really enjoyed the art aspect that they bought into it. In particular there was a work by artist Angela Strasheim in which she photographed haunting blood splatters on the walls of homes where murders or crime have happened. The effect is created by the use of 'Blue Star' solution that is applied to the areas to recall blood when it reacts with the DNA proteins. Despite deep cleaning and redecorating and many people living in the homes having no idea, the Blue Star produces eerily real splatters where once was blood.

Other artists like Weegee stood out to me, as he would tune into police frequencies so that he would always be the first to photograph the scenes. His name is a play on the word 'ouiji'.

It is an exhibition that I definitely want to go back to with someone, as it was so informative and it would be great to take in the information more.

The exhibition is extremely interesting, breaking the whole process from crime scene to court. It features real life case studies, gruesome fragments of body parts and organs, artists works that are influenced by forensics and a range of materials from medieval manuscripts to video presentations. It is an engaging exhibition that is definitely work taking the time to explore and read every bit of detail. The first room, The Crime Scene, was particularly interesting with an area focused on Jack he Ripper, another on crime photography and various other things, including a vial of gross blowfly maggots from a corpse. The grossness continued into the next room, the Morgue, in which the interesting French history of the morgue was laid out and fragments of dissected and injured organs sat in cases. I even stood through the video of the mortician talking about her role which was mega interesting.

As well as the actual knowledge that was abundant in the exhibition, I really enjoyed the art aspect that they bought into it. In particular there was a work by artist Angela Strasheim in which she photographed haunting blood splatters on the walls of homes where murders or crime have happened. The effect is created by the use of 'Blue Star' solution that is applied to the areas to recall blood when it reacts with the DNA proteins. Despite deep cleaning and redecorating and many people living in the homes having no idea, the Blue Star produces eerily real splatters where once was blood.

Other artists like Weegee stood out to me, as he would tune into police frequencies so that he would always be the first to photograph the scenes. His name is a play on the word 'ouiji'.

It is an exhibition that I definitely want to go back to with someone, as it was so informative and it would be great to take in the information more.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)