In an era where the avant garde movements of Europe wanted to stray away from traditional representation and realism in favour of a more abstracted, political artwork, New Objectivity ceased photography and the photo-book as its medium and created work that was born out of stark realism. Photographers like August Sander, Albert Renger-Patzsch and Karl Blossfeldt created narratives through images in their photo books, taking art out of the gallery space and into the sphere of the general public. The 'objective' nature of New Objectivity would suggest an un-biased nature to the movement, where the aesthetics of the object represented and the careful, often contrasting or thematic juxtaposition of these images said more than any underlying politics that influenced them. However, by using Michael Jennings text on photo-books in the Wiemar Republic, we can see how these objective and aesthetic images can have a more politically charged meaning when they are synthesised into a photo-book.

Looking at August Sander's The Face of Our Time from 1929, a selection of full age single and group portraits show a range of classes in their normal environments, starting with agriculture workers and moving thematic and systematically through urban workers, revolutionaries and capital workers. Sander's book ultimately has a focus on the population of the city, and this line of movement is symbolic of the changes that are occurring in Weimar Germany, where the city and industry are expanding. For Jennings, The Face of Our Time is both synchronic and diachronic, meaning that it is both of its time as well as charting social and historical development. Taken out of context of the photo book, the photographs are objective depictions of the everyday lives, clothes and environments of those pictured, whether it be a butcher, farmer or tycoon. When seen together in this format however, they images take on a diachronic aspect, where they track social and historical changes throughout time, starting with the dependence on the land and moving towards a higher dependence on industry and the city. 'Photography is a mosaic that becomes a synthesis only when it is presented en masse' is a way that Sander's describes the importance of the photo book, and the way that it mobilises become a diachronic piece with the ability to encapsulate society.

Straying away from people completely and focusing an interest more on the tensions of nature and industry, Renger-Patzsch's infamous photo-book The World is Beautiful from 1928 has an array of photographs that range from extreme close-ups of flowers to industrial tools and architecture. The focus on industrial photography is for Walter Benjamin and subversion of the human labour that created the commodities that Renger-Patzsch photographs, and for this reason he is emphatically against The World is Beautiful. Even the name, for Benjamin, removes all of these social relations that have come to create the commodity, however it was at the discretion of the publisher Kurt Wolff to call the photo book The World is Beautiful rather that Things which was Renger-Patzsch original vision. However, if we use Nietzsch's 'chaos theory' we can make some interesting conclusions with regards to The World is Beautiful. In chaos theory, seemingly meaningless and random events can create an enormous result when considered in retrospect. Are Renger-Patzsch's selection of images and juxtaposition of natural and synthetic images making a statement about Weimar Germany's focus on industrialisation when viewed as a synthesis of images in retrospect, or are they merely grouped due to their formal similarities, with little underlying political statement?

An irony that occurs in Benjamin's reception of the photo book occurs when we see the praise that Art Forms in Nature by Bloosfeldt received. The book which consists of close up, detail photographs of flowers and plants against a white or grey background was seen by Benjamin as hosting a great amount of artistic licence, as the photographs use tonal depth to create forms that seem almost sculptural and architectural. Ironic because the similar photographs of enlarged flowers seen by Renger-Patzsch didn't warrant the same reaction despite their similarities. The viewing of these images is described by Renger-Patzsch as 'joy before the object', where we have a strong aesthetic reaction to these uncanny objects due to the formal photographic techniques of visceral surface detail and depth of shadowing. These close-ups offer the viewer a perspective that they are not used to seeing, and gives us a sense of the camera being an extension of the human eye.

Images to use:

perryARTness

Thursday, 23 April 2015

#revision - BAUHAUS AND MAHOLY-NAGY

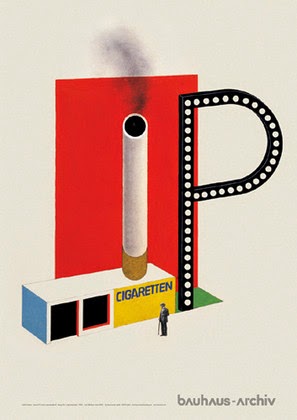

In the inter-war period, Germany was ripe for avant garde movements. The Bauhaus was started by Architect Walter Gropius in 1919 as a school that would ultimately create an all encompassing artist - 'the artist, the craftsman and the technician must become one' was a key belief of Gropius. Architecture, furniture and photography became a key areas of deign covered by the Bauhaus, and collectivised villages were created with minimalist, geometric furniture in open plan living space. This idea of collectivisation seems extreme and almost politically charged, but its aim was to remove the isolated individual instead of submit any political ideologies. The Bauhaus was based more on the belief of brining art and design into the everyday rather than politically revolution through art. Artists like Herbert Bayer designed colossal, colourful, geometric kiosks that were not realised but instead lived their life as illustrations. The images from 1924 exist as huge monuments in colourful print that dwarf the illustrated visitor. The fact that kiosks were redesigned showed the Bauhaus' desire to redesign everything in life.

An artist that wanted to redesign the way that we think about art by changing the way photography works was Lazlo Maholy-Nagy. Instead of trying to imitate art like many photographers have done, it is 'unimportant whether photography produces art or not' for Maholy-Nagy, as the mediums future worth should be what photography decides it value by. This reason is why Maholy-Nagy decides to over-perspectivise his photos, where there are multiple or extreme perspectives that at first confuse the viewer and make strange what is being depicted. Berlin Radio Tower from 1928 is a photograph taken from a birds eye viewer atop the tower, with the structure of the tower itself entering into the frame. This vertiginous metal framework appears to go on endlessly in either direction, into the ground and sky, and at once confuses and makes strange the object represented. The shadows from the settings sun are long and spread across the landscape, offering another angle of perspective. Maholy-Nagy was often criticised by his avant garde counterparts as being uncommited to any political motive in his photography, which ultimately make him as bad as the traditional artists that came before him. Devin Fore uses theories of perspective through time to understand whether this claim is true, as unlike the Constructivists or Dada, who completely negate all perspective from their work, Maholy-Nagy uses multiple perspectives. Linear perspective has come to be seen as something that is tied up in the romantic ideals of art, and to use in art during the avant garde could be seen as compliance with these traditional values. For Fore however, the artists over use of perspective still negates traditional art, as it uses its own means of rational to confuse itself.

Leda and the Swan from 1925 is a form of collage that uses the white plane as a perspectival background, with the collage forming an 'organised chaos' on the clean plane of vision. This 'chaos' offers the viewer a type of representational organisation with coherent depth and spatial volume. Instead of calling these 'photomontages', Maholy-Nagy calls them 'photoplastics', as they have much more coherence than the usual montages of the avant garde.

Images to use:

Wednesday, 22 April 2015

#revision - DADA

The Constructivists in Russia aimed to create a form of art that was in line with communist values and was available for everyone. The same could be said for Dada, however these artists were influenced by mass media, advertising and the mass commodity, which ultimately used capitalist modes of representation against itself. Artists like John Heartfield, George Grosz, Hannah Hoch and Raoul Haussman created imagery that was pro-revolutionary and anti-bourgeoisie, whilst also offering a satirical undertone.

As with many of the avant gardes, photography was utilised for its reproducibility. Artists like Hoch utilised images from mass circulated newspapers and magazines which she then collaged together to make a critique of capitalist culture. In Dada Panorama from 1919, images of the current Wiemar president wearing wellington boots are taken out of context and made strange by Hoch's placement of various other detritus of magazines and commodity culture. Hoch's technique is very layered and disjunctive, and through this technique of breaking up conventional representation, a type of subversive reality can be formed. Heartfield in particular utilises this creation of an alternative reality, but does so seamlessly. Sabine Kriebel writes about Heartfield's slaved over AIZ journal covers, which offer altered reality that is formed through seamless photomontage. This seamlessness was critised as being too reliant on formal representation by Contructivist Gustav Klutsis, however Kriebel counters this with a declaration that the ability to understand the work in such a way makes it a serious political weapon for its directness and satire.

Heartfield's utilisation of AIZ is important for the mass circulation of Dada art. AIZ is just one of many journals that were used by Dada artists, some which include Neue Jugend or the self-created 'Dada'. By engaging with these modes of circulation, the individual originality is taken away from the artwork, or as Benjamin would say the 'aura' is lost, and the works continue to exist in the world in mass. This is good for artworks that are influenced and have strong associations with propaganda and advertising, as the are made for educating the public in much the same way that political posters and campaigns do. In Millions Stand Behind Me from 1932, Heartfield engages with the political with a direct reference to Hitler's quote 'Millions stand behind me' - the millions in Hitler's case meaning the population, which Heartfield has subverted by placing a large banker putting money into Hitler's saluted arm. The clever play on words is engaging, whilst the political tone of the piece is aiming to educate the population on fascism.

As well as propaganda, advertising was important part of these artists influences. Heartfield, Grosz and Hoch all studied applied design or worked in advertising before turning to art, and therefore have a good idea of how to make an engaging work. Sherwin Simmons believes that Dada has a complex relationship with the mass commodity, in which they are working for a socialist future but using capitalist means to create it. Grosz and Heartfield presented themselves as 'manufactures of the commodity' by creating artistic greetings cards, adapting their style to suit their market for a pure exchange value. For Sherwin, by doing this the artists are 'problematising the commodity' - showing the ease at which it is possible to manipulate the market and the buyer in a capitalist society. This relationship with mass culture has come to be a trope of Dada.

As stated in earlier posts, the desire to bring art into life and life into art is a key part of the avant garde. As well as mass circulated images and the use of photography, the Dada artists also engaged with real life visuals instead of creating these montaged 'alternative realities'. After WWI, the amputee was a new visual phenomena that artists engaged with as a means of going against capitalism. Ernst Freidricks' War Against War book from 1924 showcases gruesome but frank images of the damage caused to humans due to war, stating that to 'fight against capitalism is to fight against any war' - for Freidricks, the reality of war is caused through the presence of capitalism. Grosz also directly addresses capitalisms engagement with war - in 1920 he painted War Cripples, which showed a line of war cripples on the street. This was a reality for post-war Germany, and to engage to explicitly with these visuals was an obvious anti-capitalist stance.

Images to use:

#revision - CONSTRUCTIVISM

After the October Revolution of 1917 and the overthrowing of the Tsarist regime, the Marx influenced Bolsheviks rose to power, led by Lenin. This new communist regime saw the beginning of a new type of art, that followed the avant garde praxis of brining life and into art and art into life. Through the use of photography and photo montage, to the designing of furniture and architecture, the Constructivists rethought how art and design can be integrated into life. The role of the artist was also evaluated, with El Lissitzky pushing for the artist to be an engineer and a constructor and not exist in the role of the 'genius-artist' that had come to plague art history. The communist government demanded a new social type of art, and artists like Alexander Rodchenko, Gustav Klutsis and El Lissitzky made this possible.

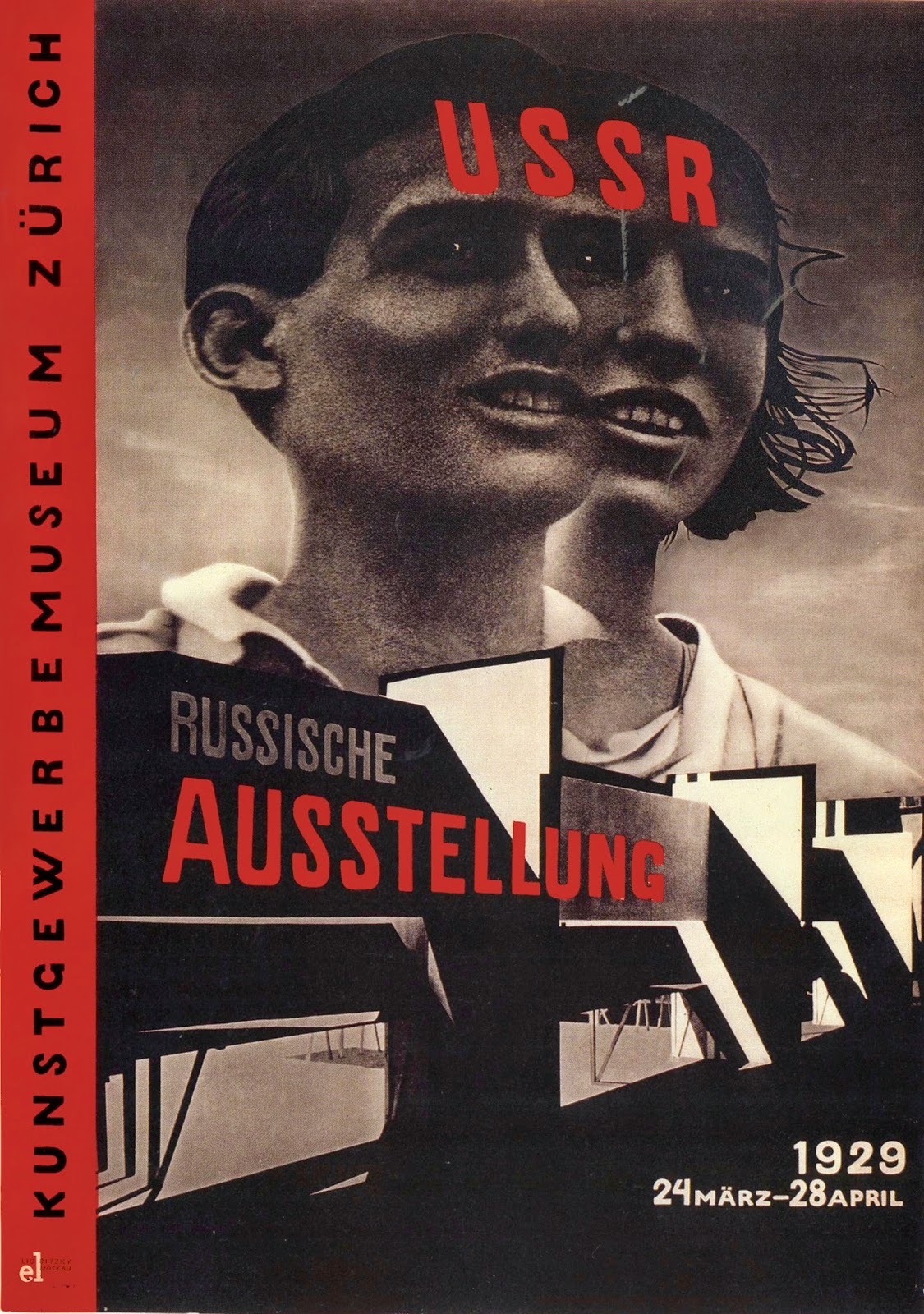

Just like the Futurists cultivated photography in their work, in Russia it became a popular medium. Osip Brik writes that photography is a more social medium, with the 'most expensive camera is still less than the cheapest painting'. For this reason, it was adopted as a new social art form, alonsgide its ability to be reproduced. Walter Benjamin highlights the importance of the ability to mechanically reproduce, and it is this reproducibility that was necessary for artists like Lissitzky and Klutsis who created posters that supported the communist government. In Klutsis' Let us Fulfill the Plan of the Great Projects from 1930, the artist uses his own hand as the focus of the montage, filled with copies of hands holding a salute. The anonymous nature of the hand allows any viewer to position themselves in the salute, and the action places the viewer in line with the communist government. A strong use of red further emphasises this connection, as does the name of the piece. Created as a poster, the ability to reproduce and be circulated is crucial to the meaning of the work - Russia had a very spread out population with high levels of illiteracy, and have a mass circulated and direct visual made this work very social. Lissitzky also uses photo montage to create posters that support the Bolsheviks, shown in his Russian Exhibition Poster from 1929, which layers the faces of both a female and a male to show the equality of the workers. Much like the Russian pavilion at the 1937 Paris International Exposition, which depicts a man and woman striding forward atop of huge column, the creation of equality in the sexes was important for communism.

The Russian Pavilion was important for signifying the desires of the Bolshevik government to the rest of the world, and was a architectural feat. Architecture was an extremely visual way of differentiating between the old and the new, and something that we can see in the ideals of Vladimir Tatlin's Monument to the Third International from 1919 which was never realised. Created from metal and glass instead of brick and mortar, this moving building was envisaged to be taller than the Eiffel tower. The movement in this monumental building was built to work was a clock, the start date 1917, symbolic of the October Revolution and the beginning of a new regime. Whilst this building was never realised (a saddening trope of the avant garde and it's desire for a utopia that ends up being missed), the photograph that was created to mimic its appearance places the traditional architecture of St Petersberg behind, emphasising the difference between the old and the new.

The artist also had a change in role, from one of genius to one of engineer. We need only look at the self portraits of two leading artists, Lissitzky and Rodchenko to see how they try and make this differentiation. In Rodchenko's self portrait photograph from 1922, we see the artist wearing a boiler suit and holding a pipe - he is taken out of the romantic ideals of the studio and put in an industrial setting, aligning him with the workers both visually and physically. Lissitzky's is very much the same in that it has a desire to show the artist as a constructor. The Constructor from 1924 is a montage of graph paper, a hand holding a compass, the end of the alphabet all over laying the artists face. Instead of an eye, the artists compass holding hand replaces, showing that the work now comes from the hand, and the mechanisms of creating perfect geometric shapes, rather than the idealised vision of the artist. The graph paper is further showing the importance of geometry and rational thought, whilst the end letter of the alphabet could be symbolic of the end of the past era, making way for a new Bolshevik art form.

Images to use:

Monday, 20 April 2015

#revision - FUTURISM

One of the most aggressively nihilistic of the avant garde movements has to be Futurism. From the violent and assertive language in their manifestos through to their fascination with war, the Futurists put their hopes in a technological future that completely destroyed traditional Italian aesthetics that came before hand. The movement began with F.T Marinetti's 1909 Futurist Manifesto that featured in La Figaro, the first amongst hundreds of manifestos that came to define the movement. In Marinetti's writing, we see the artist being re-born from a ditch into a world where technology overrides tradition, where humans have 'electric hearts' and their nerves 'demand war and despise women'. These few quotes outline the sexist and fascist undertones that the Futurists have come to be defined by, whilst also attempting to 'naturise technology and technologise nature' as Hal Foster has recently posited.

Foster tells that this desire of the Futurists to 'technologise nature' was born out of the aftermath of the wars, which showed the human bodies last of resilience to weaponry. It was time to re-think the human body and to fuse it with technology such as auto mobiles and weapons which have shown to be advanced and powerful. Bruno Munari's And thus we should set about seeking an aeroplane woman from 1939 uses photomontage to create a woman/aeroplane hybrid, showing the extreme lengths that the Futurists went to to achieve a technologised human. Even more poignant is the fact that this is a woman, which Futurists had negative feelings towards - the female gender was intertwined with ideas of nature, and therefore went against the Futurists assertion that technology was the way forward. By creating a woman out of technology, she has become far removed from the stigma of being a female that carries notions of nature.

Ideas of speed and movement were also key to the work of the Futurists, who aimed to capture dynamism or sound in their works. Chronophotography by Anton Bragaglia presented to the Futurists a form of photodynamism, where movement and speed that would usually miss the eye are caught by a camera. In The Smoker from 1911, Bragaglia captures the slow and leisurely movements of a smokers hand moving up and down, the smoke create a haze around the face. The process of the action is caught, and it is more about this movement than the subject matter that made chronophotograpy popular within Fascism. Artists like Giacomo Balla tried to capture this speed and movement on the canvas. In The Car Has Passed from 1913, visceral swoops of white and blue fragment the canvas, symbolic of the fast movement of a car that is already out of frame. The representation of the car is too fast for classic painting to pick up, racing ahead of the traditional medium, and leaving behind a trail of waves.

Movement was also captured through painterly techniques. Umberto Boccioni used divisionism in his 1910 painting The City Rises, which consists of using little strokes or dots of colour to create a dissolved effect, which give the impression of movement. By titling the figures represented at strong angles, the sense of movement is heightened. The City Rises depicts a scene of construction, where workers and horses are seen to be in a flurry of movement, and scaffolding and cranes appear in the background. It can be seen as portraying the industrialisation and technologisation of Italy that the Futurists wanted, yet the use of horses is reminiscent of the old ways of construction.

The Futurists wanted to distance themselves from the past in much stronger ways than any of the other avant gardes. Marinetti calls of the destruction of libraries and museums, 'tombs' of bourgeois consumption in a bid to move forward and create works of art that focus not on Italian classicism but instead on a bright future. Even despite being tied up with fascist links, Marinetti began to distance himself from Mussolini when the dictator started focusing on Classical Italian art.

Images to use:

Foster tells that this desire of the Futurists to 'technologise nature' was born out of the aftermath of the wars, which showed the human bodies last of resilience to weaponry. It was time to re-think the human body and to fuse it with technology such as auto mobiles and weapons which have shown to be advanced and powerful. Bruno Munari's And thus we should set about seeking an aeroplane woman from 1939 uses photomontage to create a woman/aeroplane hybrid, showing the extreme lengths that the Futurists went to to achieve a technologised human. Even more poignant is the fact that this is a woman, which Futurists had negative feelings towards - the female gender was intertwined with ideas of nature, and therefore went against the Futurists assertion that technology was the way forward. By creating a woman out of technology, she has become far removed from the stigma of being a female that carries notions of nature.

Ideas of speed and movement were also key to the work of the Futurists, who aimed to capture dynamism or sound in their works. Chronophotography by Anton Bragaglia presented to the Futurists a form of photodynamism, where movement and speed that would usually miss the eye are caught by a camera. In The Smoker from 1911, Bragaglia captures the slow and leisurely movements of a smokers hand moving up and down, the smoke create a haze around the face. The process of the action is caught, and it is more about this movement than the subject matter that made chronophotograpy popular within Fascism. Artists like Giacomo Balla tried to capture this speed and movement on the canvas. In The Car Has Passed from 1913, visceral swoops of white and blue fragment the canvas, symbolic of the fast movement of a car that is already out of frame. The representation of the car is too fast for classic painting to pick up, racing ahead of the traditional medium, and leaving behind a trail of waves.

Movement was also captured through painterly techniques. Umberto Boccioni used divisionism in his 1910 painting The City Rises, which consists of using little strokes or dots of colour to create a dissolved effect, which give the impression of movement. By titling the figures represented at strong angles, the sense of movement is heightened. The City Rises depicts a scene of construction, where workers and horses are seen to be in a flurry of movement, and scaffolding and cranes appear in the background. It can be seen as portraying the industrialisation and technologisation of Italy that the Futurists wanted, yet the use of horses is reminiscent of the old ways of construction.

The Futurists wanted to distance themselves from the past in much stronger ways than any of the other avant gardes. Marinetti calls of the destruction of libraries and museums, 'tombs' of bourgeois consumption in a bid to move forward and create works of art that focus not on Italian classicism but instead on a bright future. Even despite being tied up with fascist links, Marinetti began to distance himself from Mussolini when the dictator started focusing on Classical Italian art.

Images to use:

#revision - THE THEORY OF THE AVANTGARDE

Many of my past posts have touched on the avant garde and the neo avant garde, but in this post I would like to cumulate two of my courses to talk about theories of the avant garde. What does the term mean exactly? Was in successful and what were its main features? All of these questions are vital to our understanding of the term, and to understand that helps our understanding of many movements from the 20th century.

The avant garde has been hotly debated over by critics during the last century, with many of them have different opinions on its impact and influences. Whilst Rosalind Krauss believes originality to be at the centre of the avant garde, T.J Clark counters this stating that if originality was at the heart of the practice then, the repetitive nature of their works negates the concept. This 'originality' is born out of a political and social desire to go against tradition, and when your tradition is dominated by the institute and classic mediums of representational art, creating something that is the opposite of that is by default original. Andreas Huyssen describes the dialectical relationship with the past as a key feature of the avant garde, which is usually perceived as being nihilistic. For Huyssen, this dialectic is how it becomes possible to distance the future with the past, and new advancements with tradition. In order to create something that is so against all the usual traditions of art, new methods of making have to be deployed, and with the advancements of photography and printed media this was made possible. 'Art can no longer exist as it used to now that photography exists' - here, Benjamin highlights the importance of the existence of photography in reshaping art - his famous work The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction from 1936 tells of the importance of technology as a way of creating works of art that no longer have the 'aura' of the original, as the work is mass produced and circulated. This circulation helps to remove the work of art from the institute. giving it more exposure to a general public rather than an elite few. This was an important part of the avant garde, as gaining public awareness bought art into life and life into art, a pivotal aim of the European movements.

As well as using mechanical reproduction in their art making process, print media was used as a means of circulated manifestos created by the movements. In 1909, Le Figaro, a leading French newspaper, published F.T Marinetti's futurist manifesto, a document that took the form of a political manifesto, outlining the aims of the Futurist movement. Krauss describes the Futurists as being an example of her idea of originality in the avant-garde, as their work and ideals were born out of nothing that came before them, and instead had a direct link with technology and breaking with traditional Italian art. During the Futurist movement, some 400 manifestos were written, ranging from sculpture through to food. Their manifestos are a prime example of how the avant garde wanted to bring art into life and life into art, with a genuine belief that art can change the conciousness of society. This belief fuelled almost all of the European avant garde movements, and is a main reason as to why Peter Burger believes the historic avant gardes failed.

When Constructivism and Suprematism were shunned by Stalin in 1934 in favour of Social Realism, or Dada, Bauhaus and New Objectivity were pushed aside after Hitler's rise to power in 1933, as well as Surrealism also falling during this time due to German occupation, it seems that the avant gardes desire to change society through art wasn't achieved.

The avant garde has been hotly debated over by critics during the last century, with many of them have different opinions on its impact and influences. Whilst Rosalind Krauss believes originality to be at the centre of the avant garde, T.J Clark counters this stating that if originality was at the heart of the practice then, the repetitive nature of their works negates the concept. This 'originality' is born out of a political and social desire to go against tradition, and when your tradition is dominated by the institute and classic mediums of representational art, creating something that is the opposite of that is by default original. Andreas Huyssen describes the dialectical relationship with the past as a key feature of the avant garde, which is usually perceived as being nihilistic. For Huyssen, this dialectic is how it becomes possible to distance the future with the past, and new advancements with tradition. In order to create something that is so against all the usual traditions of art, new methods of making have to be deployed, and with the advancements of photography and printed media this was made possible. 'Art can no longer exist as it used to now that photography exists' - here, Benjamin highlights the importance of the existence of photography in reshaping art - his famous work The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction from 1936 tells of the importance of technology as a way of creating works of art that no longer have the 'aura' of the original, as the work is mass produced and circulated. This circulation helps to remove the work of art from the institute. giving it more exposure to a general public rather than an elite few. This was an important part of the avant garde, as gaining public awareness bought art into life and life into art, a pivotal aim of the European movements.

As well as using mechanical reproduction in their art making process, print media was used as a means of circulated manifestos created by the movements. In 1909, Le Figaro, a leading French newspaper, published F.T Marinetti's futurist manifesto, a document that took the form of a political manifesto, outlining the aims of the Futurist movement. Krauss describes the Futurists as being an example of her idea of originality in the avant-garde, as their work and ideals were born out of nothing that came before them, and instead had a direct link with technology and breaking with traditional Italian art. During the Futurist movement, some 400 manifestos were written, ranging from sculpture through to food. Their manifestos are a prime example of how the avant garde wanted to bring art into life and life into art, with a genuine belief that art can change the conciousness of society. This belief fuelled almost all of the European avant garde movements, and is a main reason as to why Peter Burger believes the historic avant gardes failed.

When Constructivism and Suprematism were shunned by Stalin in 1934 in favour of Social Realism, or Dada, Bauhaus and New Objectivity were pushed aside after Hitler's rise to power in 1933, as well as Surrealism also falling during this time due to German occupation, it seems that the avant gardes desire to change society through art wasn't achieved.

Sunday, 19 April 2015

#revision - ITALIAN PHOTOGRAPHY

Photography is an important part of any avant-garde movement, as it shows the inclusion of new technologies and new modes of seeing, whilst also changing the role of the artist from one who creates on a canvas or with a sculptural material to one that captures life through a lens.

Anton Bragaglia started to use chronophotography to create images that showed photo dynamism during the early 20th century, which became important for the Futurists and their fascination with speed. Photodynamism recorded the movement of a certain object or person over a specific amount of time, and is more an image of speed and movement rather than subject matter. The Smoker from 1911 tracts the slow and leisurely movement of a seated smoker, the lit match creating bright streaks across the image. As the movements create multiple images and distorts somwhat, the feeling of speed and movement is captured perfectly. Futurist painting grew out of Bragaglia's photography, trying to emulate the speed of auto mobiles. Balla's The Car Has Passed from 1913 is a prime example of photography's influence. The fragmentation of the scene and long, jagged, visceral strokes emulate the movement of the already past car, demonstrating its speed and paintings inability to keep up with the evolving speed of cars.

Photography was also adopted as a medium for politically engaged works during the 1930's, borrowing from the Surrealist and Dada's use of photo montage and photography as a political weapon against capitalism and fascism. However, these political tendencies were changed when adopted by Italian photography,and put to use to promote rather than negate the fascist government. Bruno Munari used the photo montage aesthetic in his 1934 cover for the Magazine of Fascist Aviation, where the plane one the cover is created from a montage of different images of Italian modernism such as architecture. This photo montage is clearly put to use as promoting the Fascist party and takes on the form of a 'political weapon' in much the same way that we have come to known inter-war photography.

After the war, photography began to be influenced by photojournalism, neo-realist images and the reconstruction of Italy. It also became a medium that faced challenges of being either artistic or documentary. Franco Pinna stated that 'life is meaningless until you find a story' - for him, photography had a duty as a close to nature medium to have a story and document life. For most of his photographs he assigns text to go alongside, to give the viewer an immersive experience. Maddelena La Roca from 1952 shows an astute figure and is very clearly influenced by photojounalism, which aims to capture people and places. Contrastingly, Guiseppe Cavalli believes that photography has a right to be artistic, which means a distancing from reality. In a photo Untitled, feathers are placed on a surface and photographed, their soft amorphous forms seeming at first glance unrecognisable, with further looking allowing the viewer to finally understand. Cavalli seems to take a strong influence from the photography of the Surrealists who made strange and deflected reality.

Images to use:

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)