Wednesday, 15 April 2015

#revision - NEOAVANTGARDE/MONOCROME

Using Peter Burger's and Benjamin Buchloh's opposing ideas about the neo-avant garde, I will explore why the monochrome has reappeared as an artistic practice and the various ways that the monochrome has been utilised by artists.

Peter Burger's Theory of the Avant-Garde dismisses the neo-avant-garde has being merely a repetitive form of the historic avant-garde that is void of the original, revolutionary tendencies of the earlier movement. Due to the failings of the historic avant-garde, Burger sees no possible way that by repeating their actions anything meaningful is bought around, and the artworks merely become institutionalised. We need only look at the works of Malevich and Rodchenko that occurred in the last post to see that the monochrome was a break from traditional artistic values and art practice in general. For Rodchenko in his Pure Colours of 1921, all preconceived artistic ideals were removed from the colours - no longer were these representational or emotive tools, they were simply used for their materiality on the canvas. These notions of material colour are reminisced in the work of Robert Rauschenberg, particularly his Black Paintings from 1951, where the texture and reflectivity of the paint and the materials placed under the paint were pivotal to the work, and not any of the emotive associations that are normally ingrained in colour. 'Meaning belongs to people' - this quote from Rauschenberg highlights his desire to distance himself from emotion, a particularly difficult task in a time when artists like Jackon Pollock and Mark Rothko are been revered for their emotional abstract works.

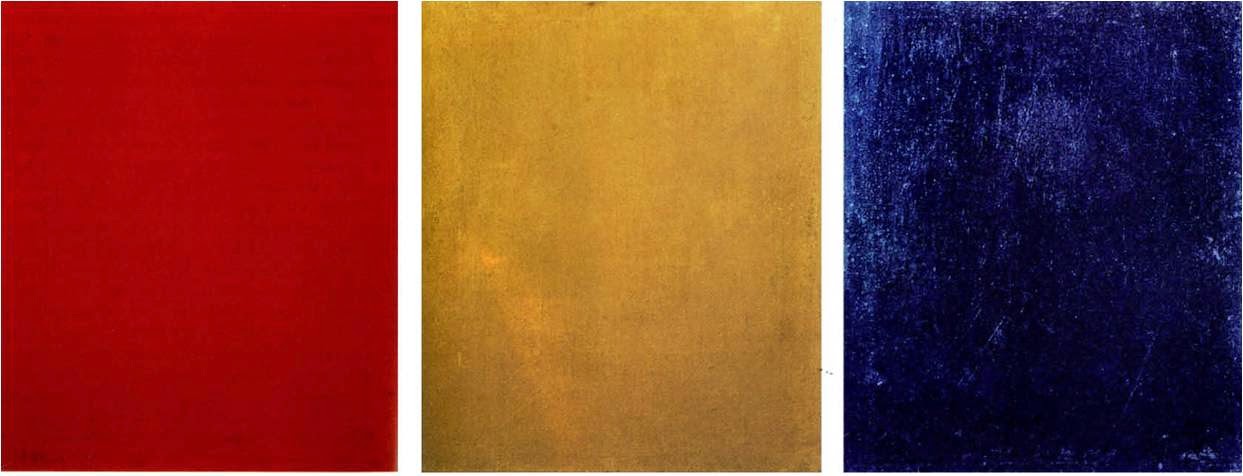

Buchloh enhances Rauschenberg's idea that instead of meaning coming from the inside of the work, it is put on the work from the outside. This interpretation of the neo-avant-garde goes against the theory of Burger, where he believes the artists are trying to assimilate the intentions of the historic avant-garde. Buchloh believes that the meanings put onto monochromes occur from the outside, and uses Yves Klein as his key example. In the spectacle that is Klein, his monochromes are sold for varying prices depending on how much importance is put on them from the outside - there are no obvious distinctions between the canvases, all the paint is rolled on to produce flat even planes and they are exhibited together, yet they sell for different prices. In creating a spectacle, the commodity value of the works goes up, and the value of these work is decided by others.

This type of monocromy was also occurring in Italy at the time, with Piero Manzoni's Achromes being deliberately void of representation and focusing instead on the materiality of the work. 'To suggest, to express, to represent: these are not problems today' - Manzoni's thoughts seem to echo those of Rauschenberg and Buchloh, where art has long been emotive and representation. By using works of varying textures such as polystyrene, wool, fur and feathers but keeping the colour white, Manzoni is playing with materiality instead of emotive associations, as does Rauschenberg in his White Paintings - they are seen as purely reductive. Reduction was always a trope of the historic avant-garde, who used it as a shock factor. In its more modern use, we can see how Burger's theory of institutionalisation has played itself out, regardless of the meaning of the works themselves.

Images to use:

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment